- Home

- Robert E. Howard

The Pirate Story Megapack: 25 Classic and Modern Tales Page 6

The Pirate Story Megapack: 25 Classic and Modern Tales Read online

Page 6

He tried to thrash the matter out, to come to a decision. It was the remembrance of Newton Foster, handsome and easy-mannered, her own kind, of her own blood, announcing his determination to go if she went, that settled Lyman’s somewhat hasty resolution. He would step aside, play the role of messenger as it had been given to him and let the play go on without him.

Love at first sight has been scoffed at by all but the scientists and young lovers themselves. Yet it is sure that certain types are attracted to each other the moment they meet, that such attractions, born of heredity, take no account of rank or fortune save as scruples and pride may creep in to break the attraction. Lyman, though he did not actually formulate the thought, sensed that a voyage with Kitty Whiting would see him tangled in a desire to win her. And what chance had he against Newton Foster, who had rallied to her side, who was versed in the ways of her world and had a hundred ways to appeal to her where Lyman might offend? A young man’s first love is often tinctured with humility, with belief in his own unworthiness compared with a girl who has exhibited especial refinement, capable of commanding equality in her mate, trained to scorn any lack of culture, educated to enjoy things of which he was ignorant. He did not know that love levels. He saw himself coarse beside her daintiness, awkward, unfit. Man to man against young Foster—that was a different matter. Put Newton Foster in the same surroundings and he had no fear of contest, but he was nothing but a sea tramp after all, a shipwrecked devil out of a job.

He got to his feet, his mind made up. He would mail the diary and drift on, straightening vanes, working as a rigger, doing odds and ends until things straightened out again and he could go to sea once more. He had thought of the Navy, but enlistments were closed. He thought now of working west, harvesting, reaching the coast, getting across the Pacific—if he had to ship as oiler or stoker—seeking fortune in the Orient where opportunities were more plentiful and white men scarcer. He had marked the street she lived on. No number was necessary for correct address. The Golden Dolphin would be sufficient, with the name.

In the hotel office he composed a short note, sincere if it did not contain all the truth:

My dear Miss Whiting:

Enclosed please find the diary with the position of the island under the date of June 27. I have no further use for the book, which is only the record of a voyage now over with, and I thought you might prefer to see the figures as originally set down. I appreciate the offer you made me, and regret I cannot see my way clear to accepting it, though I wish you all possible luck in whatever you may undertake.

I am expecting to leave Foxfield tomorrow morning so shall not have the pleasure of seeing you in the afternoon at two as I anticipated. Will you please give my regards to Miss Warner and believe me,

Sincerely yours,

James H. Lyman.

The note would do, he decided as he read the final draft. It did not say everything he wanted to but it did not say too much. She would infer, he felt sure, that he believed that the voyage had too great odds against success for him to tacitly, or otherwise, encourage it. She would not suspect that the offer of Newton Foster had anything to do with his refusal. In a week or two, whatever her conclusions, Jim Lyman would be only a shadowy person to whom she would attach a certain measure of thanks for giving her the latitude and longitude of the island.

He signed it with the feeling that he was helping to erect a permanent barrier between himself and the girl, but he believed he was doing the right thing, the best thing, in the long run. He got paper and string from the desk clerk, made a neat shipshape bundle of diary and note, had it weighed and attached the stamps. It was too late for registry but he placed additional postage and marked it Special Delivery, more as a way of insurance and means of tracing than to expedite the package. They said they would sleep late. He took it down to the post office and personally mailed it, hoping, after it had passed the lidded slot, that the messenger delivery would not awaken them too early. It thudded down into other mail like something falling into a grave. The burial of young hopes. An illuminated clock over a bank on North Street showed him the time as ten-forty.

Back at the hotel, the clerk hailed him with the news that someone had been trying hard to get him over the telephone and had finally left a number with a request for him to ring up—2895. He got connection with somewhat of a thrill. No one in all the town would be likely to ring him up but Kitty Whiting—or her cousin. But it was a man’s voice speaking, in the tones of Stephen Foster, suave, almost apologetic, in marked contract to that gentleman’s manner earlier in the evening.

“Mr. Lyman? This is Stephen Foster speaking. That news of yours swept me off my feet a bit tonight, Lyman. Little out of the usual run of business, you see. I am afraid I may have approached it too abruptly, been a bit brusque with you. If I was, I apologize. It seemed a wild idea to me; I hated to keep open my niece’s grief for her father. It is a wound already aggravated by her refusal to consider his death. Out of her love for him, of course, but unwise. Eh? Joy never kills but prolonged sorrow may. Never pays to be over optimistic.

“My son says that he does not agree with me, and we have been talking it over. I am inclined to modify my opposition if there really seems any hope at all. Also the trip may end harrowing uncertainty. If so, there is no time to lose. I wonder whether you could come up here tonight? I have some charts in my library that would help us and you would be of great practical use in discussing ways and means. It’s late, I know, but the matter is not ordinary.”

Lyman did not reply immediately, a little rushed off his feet by this change of face in Foster, Still he could hardly refuse to talk ways and means. He could stick by his decision not to go. And—

Foster was talking smoothly on. “Anyone can tell you where my place is. Out of town a little, to the south, the first road to the east after you cross the bridge over the river. About a mile, all told. I would send the car but we had some trouble with it going home and my man is tinkering with it. Can drive you back, I expect. May we expect you?”

The new attitude of Foster was flattering; he was putting the thing as a favor, Jim decided.

“I’ll start from the hotel right away.”

“Fine. And bring the figures with you. Good-by.”

He could furnish the figures all right, though not the diary. They were indelibly stamped from now on upon his recollection.

162° 37' w.

37° 19' s.

Foster, as acknowledged partner in the expedition, was entitled to them. It was natural for them to plan ahead; they would probably offer him a berth. He knew the anchorage, just where to find the ship. But he could give them all that. He propped up a resolution that was beginning to waver a bit, railed at himself for indecision, knew it was on account of the girl, knew that he might pass out of her life, but not she from his. She was like a gleam of golden metal in the commonplace strata of life.

He checked directions with the clerk, whose eyes opened with a new respect at knowing that Stephen Foster, millionaire, had called up and invited this none too prosperous guest to his house.

“You’ll find it easy enough,” said the clerk. “Only house along that road. Stands on its own grounds, back a ways. Can’t miss it.”

Jim soon decided that Foster’s ideas of direction were conservative, as might be expected from a man who invariably motored any distance further than a block. Walking briskly, it took him ten minutes to reach the bridge. The side road opened up like a tunnel, elms and maples shading it thickly. Already he seemed to have reached the open country, so abruptly did the character of the buildings change to the south of town. He had passed only scattered residences of the rich, if not of aristocracy, of Foxfield. Now and then motorcars passed him on the smooth state road, but once in this tunnel of leafage, he seemed to walk in a world remote. He rounded a bend and saw, midway in the curve, the rays of an automobile headlight spraying the trees and hedgerow on the far side. A few strides more and he was in the direct glow. The machine wa

s stationary, well to one side, seemingly out on the road proper if not in the ditch itself.

A voice called to him out of the blackness of the ray, a voice that was eager, hoarse with emotion.

“Give us a hand here, will you? The machine’s ditched and my pal’s hurt.”

Jim ran toward the car. Back of the blinding rays it was hard to distinguish anything but a vague figure. The car seemed to have slewed violently so that the rear end was down in the ditch with one wheel apparently smashed. The man who had called to him was poking about with a dim pocket flash, while the headlights were pouring out a waste of illumination.

“Here,” said the man. “At the back. The jack gave way somehow. He’s pinned under there. I’ve got a pole. Maybe one of us can lift it and drag him out. Can you handle that rock? Make a lever out of it?”

His flashlight showed a big stone in the ditch of the type from which stone walls are made.

Jim bent to lift it. Something struck him at the back of his head where the skull meets vertebrae. Golden lights flashed out like an exploding firework and gave way to blackness and oblivion as he pitched forward.

IV

Action

The first conscious sensation Jim recovered was that he was being slowly smothered; the second that he was riding fast, being jolted over rough side roads, presumably in an automobile. He reacted slowly, retarded by a dull headache that seemed to sap the vitality out of him. He was bound ankle and wrist, his arms strapped to his sides and a strap about his knees. They had made a good job of securing him, and not content with rope and leather, they had set him into a canvas sack, a sort of duffle bag into which he had been thrust feet first with the throat of the bad tight about his hips with draw strings. A second bag had been brought down over head and shoulders until it overlapped the first. He could breathe, but the air he got to his lungs was hot and smelly and none too pure. The necessary first aid supply of oxygen was deteriorated; he was like an engine trying to make power on bad gasoline.

It was hard to think consecutively but the searchlight of his objective reasoning played persistently upon the fact—it seemed to be a fact—that he had been deliberately waylaid on the road to Foster’s. No one except the clerk at the hotel knew where he was going, outside of Stephen Foster, his son, and perhaps his household. If highway robbery had been their purpose his unknown assailants showed poor judgment in selecting him. They had had excellent chance to gauge him as he advanced in the full beams of the automobile headlights and Lyman was conscious that he looked like anything but a wealth carrier. On the other hand, if they had been deliberately waiting for him to come along, meaning to make sure of their man against any other person who might travel that lonely way at that time of night, the plan adopted was an excellent one. The wrong and curious passerby could have been dismissed with an assurance that the car was all right—as it undoubtedly was. It was more than likely he was now traveling in the same machine. The only slip up, a remote chance, would have been that Jim should arrive on the scene in company with someone else, and doubtless they had provided for that.

What was their purpose? He suspected Stephen Foster. Would Foster go to the length of having him knocked on the head and kidnapped in order to prevent his niece getting the figures and starting off on the expedition? That Foster was quite capable of such high-handed and unscrupulous procedure, he believed, remembering his impressions of the man, his cold eyes and letterbox mouth. Or was it with reason more sinister? Here Lyman abandoned all attempts at working things out under the circumstances. His head ached intolerably and he was suffering from thirst. But anger accumulated in him, awaiting the chance for action.

Hour after hour, it seemed, they jolted over the roads. There were plenty of good state roads in the region, he knew. They must be purposely choosing unfrequented ways, running like bootleggers to escape observation. Jim prayed that some prowling federal officer or state policeman might halt and search the car. He seemed to be on the floor of the tonneau, otherwise unoccupied.

Torture increased in his cramped limbs as circulation grew sluggish; he lost feeling in them. Still the car sped on through the night.

It stopped at last after climbing a steep hillside; the engine was shut off; the door of the tonneau opened and Jim was lifted, an inert bundle, and deposited on the ground. He could not even draw up his knees. He could see nothing. He was not gagged, but efficiently muffled by the sacking. Through it he could not distinguish what the men who had brought him were saying.

They picked him up again and carried him a little distance. Then the top sack was withdrawn. Jim’s eyes, slow to accept the quick change of light, made out ancient and cobwebby rafters high above his head with wisps of hay showing here and there, festoons of old rope, hooks, a pulley. He was on the floor of a barn. There was the reek of old manure. The dawn had broken and the upland air was cold. Twisting his neck, he saw his captors. One wore the leather hood of aviator and motorcyclist; the other had the wide peak of a cap well drawn down. Both wore big goggles with leather nose-pieces. One was unshaven, bristly; the other wore a square beard. A flask passed, Jim caught the smell of whisky. The chill air had cleared his head and he formulated a course of action. Good nature could lose him nothing if he could simulate it and cover the smouldering wrath that possessed him. And a sup of liquor with its quick stimulus might aid him. He was willing to take a chance on its quality.

“You might give me a swig of that,” he said. “And loosen up a hole or two. My arms and legs are numb.” The man with the hood looked down at him with eyes gleaming sardonically back of the colored lenses. Then he laughed.

“You’re a cool customer,” he said.

“Too cool in this air, with my blood stopped. You’re not aiming to murder me, I figure, or you wouldn’t have spent so much gas on me. If you aim to keep me alive, let me have a drink.”

“Costs too much and there ain’t more’n enough for two,” demurred the bearded man.

“He can have my whack,” answered the other. “You got him tied up too hard, Bill. No sense in that.”

“He’s worth money delivered. I’m proposin’ to deliver him.”

The man with the hood nevertheless loosened the straps a hole, slid off the lower sack, eased up Jim’s ankles and supporting him, set the flask to his lips. Jim gulped at the stuff. He needed it. Pain shot through every nerve and artery as his heart, reacting to the kick of the liquor, urged the blood through to proper circulation. He lay back, fighting it as the two moved off, holding a consultation of which he caught snatches. It seemed based upon the question whether one of them should remain with Jim or both go to town. He strained his ears in vain to catch sound of the name of it. The pain in his limbs grew less acute. And while the back of his head was sore, it no longer throbbed.

He was miles from Foxfield. He figured they had averaged at least twenty-five miles an hour through the night for about six hours. And there would be no one to bother about him, save at the hotel where his few belongings were left. The clerk might well think he had left them rather than pay his bill. He had told Kitty Whiting that he was going away.

He was to be delivered somewhere and was considered a valuable package; that was a certain amount of information. Delivered to whom?

“Foster pay you well for this job?” he hazarded as the men came back.

“Shut up,” said the one called Bill, now in ill humor. “I never heard of Foster, so quit ravin’. My partner’s goin’ down to send a wire and get some grub. He’ll bring some up to us. You’ll eat, but quit your gabbin’ because it won’t do you a mite of good. Hey, Bud, we can’t leave him lyin’ on the floor. Where you goin’ to stow him?” The prospect of food sounded good to Jim. They might untie his hands. If he were left alone he might clear his bonds himself. He was resolved to wait for the first chance for freedom and then to make a desperate bid for it. He lay quiet while the pair prospected. But he put up a desperate protest when they came back and picked up the sack that had gone over his head.<

br />

“No sense in smothering me,” he said. The pair did not seem unnecessarily brutal. They had not actually mistreated him since that first smash on the base of his skull. Bill was the harder customer of the two. “I’ll not yell if you give me a chance to breathe,” said Jim.

“You yell and I’ll tap you over the head. It won’t be a love tap, either,” said Bill. “We’ll give you a tryout. Come on, Bud.”

They carried him down an alley between two rows of empty cow stanchions. Overhead he could see gaps in the roof shingles. He imagined the place to be the outweathered barn of an abandoned farm. Bill opened a door and he was thrust into a dark place smelling of mouldy grain. It was less than six feet square, too small for him to lie extended. The door closed on a bare glimpse of walls close sealed with tongue and groove, a chute leading upward, and two big bins against the far side. There was a click of latch or staple and he was left alone.

As a rule Jim was even tempered. He had bursts of dynamic fury that he could muster on occasions when rage was needed as lash and spur to urge others to vital effort. Now he had hard work to control his wrath. It steadily mounted until he saw red in the black grain closet, flashes and whirls of red. To get loose, to pin this outrage upon somebody and take it out of their hide was his one wish. That this capture was in some way connected with the Golden Dolphin and the proposed trip he did not doubt. Casting about, he wondered whether the maid of Kitty Whiting’s, with her insatiable curiosity, had anything to do with it. He remembered the skeleton with the cleft skull, the suggestion from Lynda Warner that she was not surprised at foul play. Though he had not looked at it before from this standpoint, he realized that if there were pearls hidden in a secret place aboard the ship, then his information was indeed valuable.

Foster had told him to bring his figures. Perhaps they had searched him for his diary while he was unconscious. He dismissed the idea. If they were agents of Foster, and Foster wanted to get at the figures, the simplest way would have been the best. As an acknowledged partner Jim could hardly have refused to give Foster the position. Now it was different. Wild horses should not drag the information from him, if that was what they were after. And it was the only valuable, enviable thing he possessed.

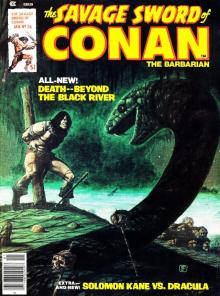

Beyond the Black River

Beyond the Black River Gods of the North

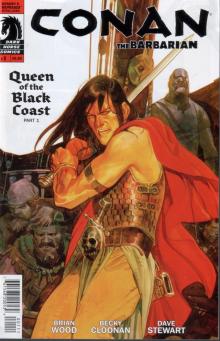

Gods of the North Queen of the Black Coast

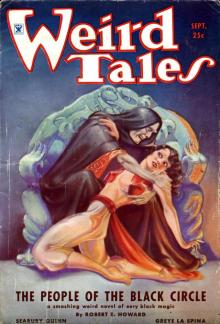

Queen of the Black Coast The People of the Black Circle

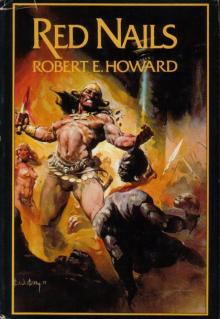

The People of the Black Circle Red Nails

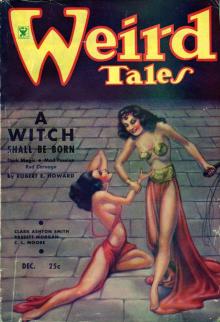

Red Nails A Witch Shall Be Born

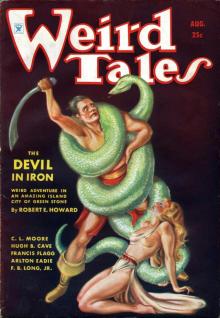

A Witch Shall Be Born The Devil in Iron

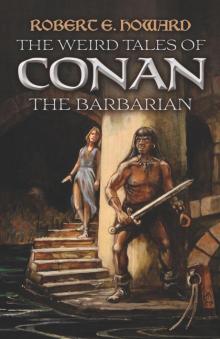

The Devil in Iron The Weird Tales of Conan the Barbarian

The Weird Tales of Conan the Barbarian The Bloody Crown of Conan

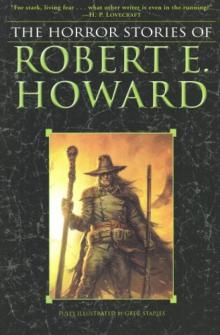

The Bloody Crown of Conan The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard

The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard Conan the Conqueror

Conan the Conqueror Conan the Barbarian

Conan the Barbarian Shadows in the Moonlight

Shadows in the Moonlight The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane

The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane Bran Mak Morn: The Last King

Bran Mak Morn: The Last King The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume One: Crimson Shadows

The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume One: Crimson Shadows The Best of Robert E. Howard: Crimson Shadows (Volume 1)

The Best of Robert E. Howard: Crimson Shadows (Volume 1) Black Hounds of Death

Black Hounds of Death Jewels of Gwahlur

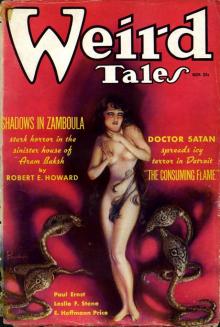

Jewels of Gwahlur Shadows in Zamboula

Shadows in Zamboula The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian

The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian The Mythos Tales

The Mythos Tales The Hour of the Dragon

The Hour of the Dragon The Hyborian Age

The Hyborian Age El Borak and Other Desert Adventures

El Borak and Other Desert Adventures The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1 The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1

The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1 The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1 El Borak: The Complete Tales

El Borak: The Complete Tales Kull: Exile of Atlantis

Kull: Exile of Atlantis The Conquering Sword of Conan

The Conquering Sword of Conan The Conan Compendium

The Conan Compendium The Conan Chronicles: Volume 1: The People of the Black Circle

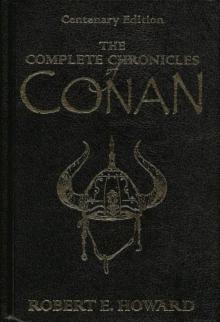

The Conan Chronicles: Volume 1: The People of the Black Circle The Complete Chronicles of Conan: Centenary Edition

The Complete Chronicles of Conan: Centenary Edition Tales of Bran Mak Morn (Serapis Classics)

Tales of Bran Mak Morn (Serapis Classics) Delphi Works of Robert E. Howard (Illustrated) (Series Four)

Delphi Works of Robert E. Howard (Illustrated) (Series Four) Conan the Barbarian: The Stories That Inspired the Movie

Conan the Barbarian: The Stories That Inspired the Movie People of the Dark Robert Ervin Howard

People of the Dark Robert Ervin Howard Grim Lands

Grim Lands Wings in the Night

Wings in the Night Gardens of Fear

Gardens of Fear A Thunder of Trumpets

A Thunder of Trumpets Detective of the Occult

Detective of the Occult Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures

Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures Historical Adventures

Historical Adventures Moon of Skulls

Moon of Skulls The Robert E. Howard Omnibus: 97 Collected Stories

The Robert E. Howard Omnibus: 97 Collected Stories The Pirate Story Megapack: 25 Classic and Modern Tales

The Pirate Story Megapack: 25 Classic and Modern Tales The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 2

The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 2 The Conan Chronicles, Vol. 1: The People of the Black Circle

The Conan Chronicles, Vol. 1: The People of the Black Circle Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures M

Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures M The Complete Chronicles of Conan

The Complete Chronicles of Conan Conan the Barbarian: The Chronicles of Conan (collected short stories)

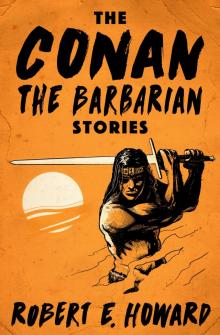

Conan the Barbarian: The Chronicles of Conan (collected short stories) The Conan the Barbarian Stories

The Conan the Barbarian Stories The Best Horror Stories of

The Best Horror Stories of Tigers Of The Sea cma-4

Tigers Of The Sea cma-4 The Hours of the Dragon

The Hours of the Dragon Conan the Cimmerian: The Complete Tales (Trilogus Classics)

Conan the Cimmerian: The Complete Tales (Trilogus Classics) Collected Western Stories of Robert E. Howard (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics)

Collected Western Stories of Robert E. Howard (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics) The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 1

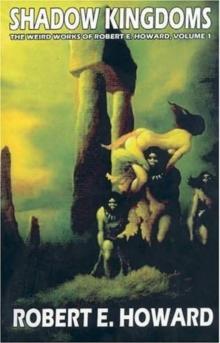

The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 1 Shadow Kingdoms

Shadow Kingdoms