- Home

- Robert E. Howard

Tigers Of The Sea cma-4

Tigers Of The Sea cma-4 Read online

Tigers Of The Sea

( Cormac Mac Art - 4 )

Robert E Howard

Tigers Of The Sea

Robert E Howard

"Tigers of the sea! Men with the hearts of wolves and thews of fire and steel! Feeders of ravens whose only joy lies in slaying and dying! Giants to whom the death-song of the sword is sweeter than the love-song of a girl!"

The tired eyes of King Gerinth were shadowed.

"This is no new tale to me; for a score of years such men have assailed my people like hunger-maddened wolves."

"Take a page from Caesar's book," answered Donal the minstrel as he lifted a wine goblet and drank deep. "Have we not read in the Roman books how he pitted wolf against wolf? Aye-that way he conquered our ancestors, who in their day were wolves also."

"And now they are more like sheep," murmured the king, a quiet bitterness in his voice. "In the years of the peace of Rome, our people forgot the arts of war. Now Rome has fallen and we fight for our lives-and cannot even protect our women."

Donal set down the goblet and leaned across the finely carved oak table.

"Wolf against wolf!" he cried. "You have told me-as well I knew!-that no warriors could be spared from the borders to search for your sister, the princess Helen-even if you knew where she is to be found. Therefore, you must enlist the aid of other men-and these men I have just described to you are as superior in ferocity and barbarity to the savage Angles that assail us as the Angles themselves are superior to our softened peasantry."

"But would they serve under a Briton against their own blood?" demurred the king. "And would they keep faith with me?"

"They hate each other as much as we hate them both," answered the minstrel. "Moreover, you can promise them the reward-only when they return with the princess Helen."

"Tell me more of them," requested King Gerinth.

"Wulfhere the Skull-splitter, the chieftain, is a red-bearded giant like all his race. He is crafty in his way, but leads his Vikings mainly because of his fury in battle. He handles his heavy, long shafted axe as lightly as if it were a toy, and with it he shatters the swords, shields, helmets and skulls of all who oppose him. When Wulfhere crashes through the ranks, stained with blood, his crimson beard bristling and his terrible eyes blazing and his great axe clotted with blood and brains, few there are who dare face him.

"But it is on his righthand man that Wulfhere depends for advice and council. That one is crafty as a serpent and is known to us Britons of old-for he is no Viking at all by birth, but a Gael of Erin, by name Cormac Mac Art, called an Cliuin, or the Wolf. Of old he led a band of Irish reivers and harried the coasts of the British Isles and Gaul and Spain-aye, and he preyed also on the Vikings themselves, But civil war broke up his band and he joined the forces of Wulfhere-they are Danes and dwell in a land south of the people who are called Norsemen.

"Cormac Mac Art has all the guile and reckless valor of his race. He is tall and rangy, a tiger where Wulfhere is a wild bull. His weapon is the sword, and his skill is incredible. The Vikings rely little on the art of fencing; their manner of fighting is to deliver mighty blows with the full sweep of their arms. Well, the Gael can deal a full arm blow with the best of them, but he favors the point. In a world where the old-time skill of the Roman swordsman is almost forgotten, Cormac Mac Art is well-nigh invincible. He is cool and deadly as the wolf for which he is named, yet at times, in the fury of battle, a madness comes upon him that transcends the frenzy of the Berserk. At such times he is more terrible than Wulfhere, and men who would face the Dane flee before the blood-lust of the Gael."

King Gerinth nodded. "And could you find these men for me?"

"Lord King, even now they are within reach. In a lonely bay on the western coast, in a little-frequented region, they have beached their dragon-ship and are making sure that it is fully sea-worthy before moving against the Angles. Wulfhere is no sea-king; he has but one ship-but so swiftly he moves and so fierce is his crew that the Angles, Jutes and Saxons fear him more than any of their other foes. He revels in battle. He will do as you wish him, if the reward is great enough."

"Promise him anything you will, answered Gerinth. "It is more than a princess of the realm that has been stolen-it is my little sister."

His fine, deeply-lined face was strangely tender as he spoke.

"Let me attend to it," said Donal, refilling his goblet. "I know where these Vikings are to be found. I can pass among them-but I tell you before I start that it will take your Majesty's word, from your own lips, to convince Cormac Mac Art of-anything! Those Western Celts are more wary than the Vikings themselves."

Again King Gerinth nodded. He knew that the minstrel had walked strange paths and that though he was loquacious on most subjects, he was tight-lipped on others. Donal was blest or cursed with a strange and roving mind and his skill with the harp, opened many doors to him that axes could not open. Where a warrior had died, Donal of the Harp walked unscathed. He knew well many fierce sea-kings who were but grim legends and myths to most of the people of Britain, but Gerinth had never had cause to doubt the minstrel's loyalty.

II.

Wulfhere of the Danes fingered his crimson beard and scowled abstractedly. He was a giant; his breast muscles bulged like twin shields under his scale mail corselet. The horned helmet on his head added to his great height, and with his huge hand knotted about the long shaft of a great axe he made a picture of rampant barbarism not easily forgotten. But for all his evident savagery, the chief of the Danes seemed slightly bewildered and undecided. He turned and growled a question to a man who sat near.

This man was tall and rangy. He was big and powerful, and though he lacked the massive bulk of the Dane, he more than made up for it by the tigerish litheness that was apparent in his every move. He was dark, with a smooth-shaven face and square-cut black hair. He wore none of the golden armlets or ornaments of which the Vikings were so fond. His mail was of chain mesh and his helmet, which lay beside him, was crested with flowing horse-hair.

"Well, Cormac," growled the pirate chief, "what think you?"

Cormac Mac Art did not reply directly to his friend. His cold, narrow, grey eyes gazed full into the blue eyes of Donal the minstrel. Donal was a thin man of more than medium height. His wayward unruly hair was yellow. Now he bore neither harp nor sword and his dress was whimsically reminiscent of a court jester. His thin, patrician face was as inscrutable at the moment as the sinister, scarred features of the Gael.

"I trust you as much as I trust any man," said Cormac, "but I must have more than your mere word on the matter. How do I know that this is not some trick to send us on a wild goose chase, or mayhap into a nest of our enemies? We have business on the east coast of Britain-"

"The matter of which I speak will pay you better than the looting of some pirate's den," answered the minstrel. "If you will come with me, I will bring you to the man who may be able to convince you. But you must come alone, you and Wulfhere."

"A trap," grumbled the Dane. "Donal, I am disappointed in you-"

Cormac, looking deep into the minstrel's strange eyes, shook his head slowly.

"No, Wulfhere; if it be a trap, Donal too is duped and that I cannot believe."

"If you believe that," said Donal, "why can you not believe my mere word in regard to the other matter?"

"That is different," answered the reiver. "Here only my life and Wulfhere's is involved. The other concerns every member of our crew. It is my duty to them to require every proof. I do not think you lie; but you may have been lied to."

"Come, then, and I will bring you to one whom you will believe in spite of yourself."

Cormac rose from the great rock whereon he had been sitting and donned his

helmet. Wulfhere, still grumbling and shaking his head, shouted an order to the Vikings who sat grouped about a small fire a short distance away, cooking a haunch of venison. Others were tossing dice in the sand, and others still working on the dragonship which was drawn up on the beach. Thick forest grew close about this cove, and that fact, coupled with the wild nature of the region, made it an ideal place for a pirate's rendezvous.

"All sea-worthy and ship-shape," grumbled Wulfhere, referring to the galley. "On the morrow we could have sailed forth on the Viking path again-"

"Be at ease, Wulfhere," advised the Gael. "If Donal's man does not make matters sufficiently clear for our satisfaction, we have but to return and take the path."

"Aye-if we return."

"Why, Donal knew of our presence. Had he wished to betray us, he could have led a troop of Gerinth's horsemen upon us, or surrounded us with British bowmen. Donal, at least, I think, means to deal squarely with us as, he has done in the past. It is the man behind Donal I mistrust."

The three had left the small bay behind them and now walked along in the shadow of the forest. The land tilted upward rapidly and soon the forest thinned out to straggling clumps and single gnarled oaks that grew between and among huge boulders-boulders broken as if in a Titan's play. The landscape was rugged and wild in the extreme. Then at last they rounded a cliff and saw a tall man, wrapped in a purple cloak, standing beneath a mountain oak. He was alone and Donal walked quickly toward him, beckoning his companions to follow. Cormac showed no sign of what he thought, but Wulfhere growled in his beard as he gripped the shaft of his axe and glanced suspiciously on all sides, as if expecting a horde of swordsmen to burst out of ambush. The three stopped before the silent man and Donal doffed his feathered cap. The man dropped his cloak and Cormac gave a low exclamation.

"By the blood of the gods! King Gerinth himself!"

He made no movement to kneel or to uncover his head, nor did Wulfhere. These wild rovers of the sea acknowledged the rule of no king. Their attitude was the respect accorded a fellow warrior; that was all. There was neither insolence nor deference in their manner, though Wulfhere's eyes did widen slightly as he gazed at the man whose keen brain and matchless valor had for years, and against terrific odds, stemmed the triumphant march of the Saxons to the Western sea.

The Dane saw a tall, slender man with a weary aristocratic face and kindly grey eyes. Only in his black hair was the Latin strain in his veins evident. Behind him lay the ages of a civilization now crumbled to the dust before the onstriding barbarians. He represented the last far-flung remnant of Rome's once mighty empire, struggling on the waves of barbarism which had engulfed the rest of that empire in one red inundation. Cormac, while possessing the true Gaelic antipathy for his Cymric kin in general, sensed the pathos and valor of this brave, vain struggle, and even Wulfhere, looking into the far-seeing eyes of the British king, felt a trifle awed. Here was a people, with their back to the wall, fighting grimly for their lives and at the same time vainly endeavoring to uphold the culture and ideals of an age already gone forever. 'The gods of Rome had faded under the ruthless heel of Goth and Vandal. Flaxen-haired savages reigned in the purple halls of the vanished Caesars. Only in this far-flung isle a little band of Romanized Celts clung to the traditions of yesterday.

"These are the warriors, your Majesty," said Donal, and Gerinth nodded and thanked him with the quiet courtesy of a born nobleman.

"They wish to hear again from your lips what I have told them," said the bard.

"My friends," said the king quietly, "I come to ask your aid. My sister, the princess Helen, a girl of twenty years of age, has been stolen-how, or by whom, I do not know. She rode into the forest one morning attended only by her maid and a page, and she did not return. It was on one of those rare occasions when our coasts were peaceful; but when search parties were sent out, they found the page dead and horribly mangled in a small glade deep in the forest. The horses were found later, wandering loose, but of the princess Helen and her maid there was no trace. Nor was there ever a trace found of her, though we combed the kingdom from border to sea. Spies sent among the Angles and Saxons found no sign of her, and we at last decided that she had been taken captive and borne away by some wandering band of sea-farers who, roaming inland, had seized her and then taken to sea again.

"We are helpless to carry on such a search as must be necessary if she is to be found. We have no ships-the last remnant of the British fleet was destroyed in the sea-fight off Cornwall by the Saxons. And if we had ships, we could not spare the men to man them, not even for the princess Helen. The Angles press hard on our eastern borders and Cerdic's brood raven upon us from the south. In my extremity I appeal to you. I cannot tell you where to look for my sister. I cannot tell you how to recover her if found. I can only say: in the name of God, search the ends of the world for her, and if you find her, return with her and name your price."

Wulfhere glanced at Cormac as he always did in matters that required thought.

"Better that we set a price before we go," grunted the Gael.

"Then you agree?" cried the king, his fine face lighting.

"Not so fast," returned the wary Gael. "Let us first bargain. It is no easy task you set us: to comb the seas for a girl of whom nothing is known save that she was stolen. How if we search the oceans and return empty-handed?"

"Still I will reward you," answered the king. "I have gold in plenty. Would I could trade it for warriors-but I have Vortigern's example before me."

"If we go and bring back the princess, alive or dead," said Cormac, "you shall give us a hundred pounds of virgin gold, and ten pounds of gold for each man we lose on the voyage. If we do our best and cannot find the princess, you shall still give us ten pounds for every man slain in the search, but we will waive further reward. We are not Saxons, to haggle over money. Moreover, in either event you will allow us to overhaul our long ship in one of your bays, and furnish us with material enough to replace such equipment as may be damaged during the voyage. Is it agreed?"

"You have my word and my hand on it," answered the king, stretching out his arm, and as their hands met Cormac felt the nervous strength in the Briton's fingers.

"You sail at once?"

"As soon as we can return to the cove."

"I will accompany you," said Donal suddenly, "and there is another who would come also."

He whistled abruptly-and came nearer to sudden decapitation than he guessed; the sound was too much like a signal of attack to leave the wolf-like nerves of the sea-farers untouched. Cormac and Wulfhere, however, relaxed as a single man strode from the forest.

"This is Marcus, of a noble British house," said Donal, "the betrothed of the princess Helen. He too will accompany us if he may."

The young man was above medium height and well built. He was in full chain mail armor and wore the crested helmet of a legionary; a straight thrusting-sword was girt upon him. His eyes were grey, but his black hair and the faint olive-brown tint of his complexion showed that the warm blood of the South ran far more strongly in his veins than in those of his king. He was undeniably handsome, though now his face was shadowed with worry.

"I pray you will allow me to accompany you." He addressed himself to Wulfhere. "The game of war is not unknown to me-and waiting here in ignorance of the fate of my promised bride would be worse to me than death."

"Come if you will," growled Wulfhere. "It's like we'll need all the swords we can muster before the cruise is over. King Gerinth, have you no hint whatever of who took the princess?"

"None. We found only a single trace of anything out of the ordinary in the forests. Here it is."

The king drew from his garments a tiny object and passed it to the chieftain. Wulfhere stared, unenlightened, at the small, polished flint arrowhead which lay in his huge palm. Cormac took it and looked closely at it. His face was inscrutable but his cold eyes flickered momentarily. Then the Gael said a strange thing:

"I will not shave today, af

ter all."

III.

The fresh wind filled the sails of the dragonship and the rhythmic clack of many oars answered the deep-chested chant of the rowers. Cormac Mac Art, in full armor, the horse-hair of his helmet floating in the breeze, leaned on the rail of the poop-deck. Wulfhere banged his axe on the deal planking and roared an unnecessary order at the steersman.

"Cormac," said the huge Viking, "who is king of Britain?"

"Who is king of Hades when Pluto is away?" asked the Gael.

"Read me no runes from your knowledge of Roman myths," growled Wulfhere.

"Rome ruled Britain as Pluto rules Hades," answered Cormac. "Now Rome has fallen and the lesser demons are battling among themselves for mastery. Some eighty years ago the legions were withdrawn from Britain when Alaric and his Goths sacked the imperial city. Vortigern, was king of Britain-or rather, made himself so when the Britons had to look to themselves for aid. He let the wolves in, himself, when he hired Hengist and Horsa and their Jutes to fight off the Picts, as you know. The Saxons and Angles poured in after them like a red wave and Vortigern fell. Britain is split into three Celtic kingdoms now, with the pirates holding all the eastern coast and slowly but surely forcing their way westward. The southern kingdom, Damnonia and the country extending to Caer Odun, is ruled over by Uther Pendragon. The middle kingdom, from Uther's lines to the foot of the Cumbrian Mountains, is held by Gerinth. North of his kingdom is the realm known by the Britons as Strath-Clyde-King Garth's domain. His people are the wildest of all the Britons, for many of them are tribes which were never fully conquered by Rome. Also, in the most westwardly tip of Damnonia and among the western mountains of Gerinth's land are barbaric tribes who never acknowledged Rome and do not now acknowledge any one of the three kings. The whole land is prey to robbers and bandits, and the three kings are not always at peace among themselves, owing to Uther's waywardness, which is tinged with madness, and to Garth's innate savagery. Were it not that Gerinth acts as a buffer between them, they would have been at each other's throats long ago.

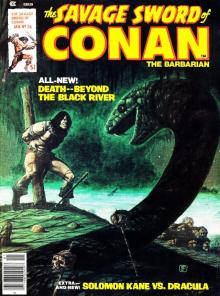

Beyond the Black River

Beyond the Black River Gods of the North

Gods of the North Queen of the Black Coast

Queen of the Black Coast The People of the Black Circle

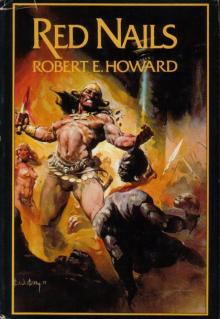

The People of the Black Circle Red Nails

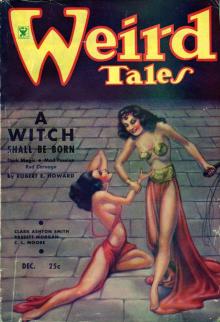

Red Nails A Witch Shall Be Born

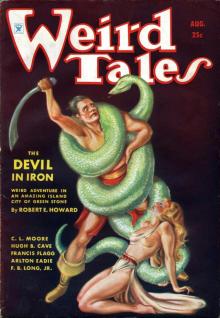

A Witch Shall Be Born The Devil in Iron

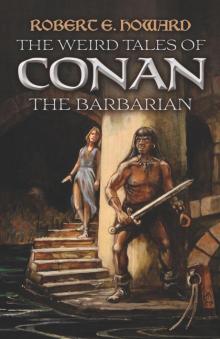

The Devil in Iron The Weird Tales of Conan the Barbarian

The Weird Tales of Conan the Barbarian The Bloody Crown of Conan

The Bloody Crown of Conan The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard

The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard Conan the Conqueror

Conan the Conqueror Conan the Barbarian

Conan the Barbarian Shadows in the Moonlight

Shadows in the Moonlight The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane

The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane Bran Mak Morn: The Last King

Bran Mak Morn: The Last King The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume One: Crimson Shadows

The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume One: Crimson Shadows The Best of Robert E. Howard: Crimson Shadows (Volume 1)

The Best of Robert E. Howard: Crimson Shadows (Volume 1) Black Hounds of Death

Black Hounds of Death Jewels of Gwahlur

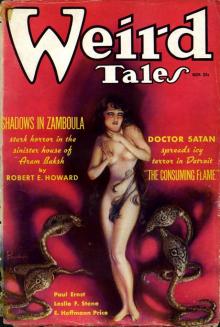

Jewels of Gwahlur Shadows in Zamboula

Shadows in Zamboula The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian

The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian The Mythos Tales

The Mythos Tales The Hour of the Dragon

The Hour of the Dragon The Hyborian Age

The Hyborian Age El Borak and Other Desert Adventures

El Borak and Other Desert Adventures The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1 The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1

The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1 The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1 El Borak: The Complete Tales

El Borak: The Complete Tales Kull: Exile of Atlantis

Kull: Exile of Atlantis The Conquering Sword of Conan

The Conquering Sword of Conan The Conan Compendium

The Conan Compendium The Conan Chronicles: Volume 1: The People of the Black Circle

The Conan Chronicles: Volume 1: The People of the Black Circle The Complete Chronicles of Conan: Centenary Edition

The Complete Chronicles of Conan: Centenary Edition Tales of Bran Mak Morn (Serapis Classics)

Tales of Bran Mak Morn (Serapis Classics) Delphi Works of Robert E. Howard (Illustrated) (Series Four)

Delphi Works of Robert E. Howard (Illustrated) (Series Four) Conan the Barbarian: The Stories That Inspired the Movie

Conan the Barbarian: The Stories That Inspired the Movie People of the Dark Robert Ervin Howard

People of the Dark Robert Ervin Howard Grim Lands

Grim Lands Wings in the Night

Wings in the Night Gardens of Fear

Gardens of Fear A Thunder of Trumpets

A Thunder of Trumpets Detective of the Occult

Detective of the Occult Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures

Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures Historical Adventures

Historical Adventures Moon of Skulls

Moon of Skulls The Robert E. Howard Omnibus: 97 Collected Stories

The Robert E. Howard Omnibus: 97 Collected Stories The Pirate Story Megapack: 25 Classic and Modern Tales

The Pirate Story Megapack: 25 Classic and Modern Tales The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 2

The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 2 The Conan Chronicles, Vol. 1: The People of the Black Circle

The Conan Chronicles, Vol. 1: The People of the Black Circle Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures M

Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures M The Complete Chronicles of Conan

The Complete Chronicles of Conan Conan the Barbarian: The Chronicles of Conan (collected short stories)

Conan the Barbarian: The Chronicles of Conan (collected short stories) The Conan the Barbarian Stories

The Conan the Barbarian Stories The Best Horror Stories of

The Best Horror Stories of Tigers Of The Sea cma-4

Tigers Of The Sea cma-4 The Hours of the Dragon

The Hours of the Dragon Conan the Cimmerian: The Complete Tales (Trilogus Classics)

Conan the Cimmerian: The Complete Tales (Trilogus Classics) Collected Western Stories of Robert E. Howard (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics)

Collected Western Stories of Robert E. Howard (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics) The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 1

The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 1 Shadow Kingdoms

Shadow Kingdoms