- Home

- Robert E. Howard

The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 2

The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 2 Read online

THE FULLY ILLUSTRATED ROBERT E. HOWARD LIBRARY

from Del Rey Books

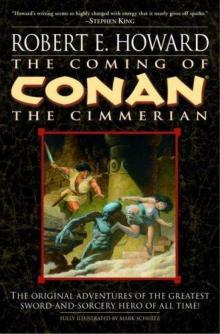

The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian

The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane

The Bloody Crown of Conan

Bran Mak Morn: The Last King

The Conquering Sword of Conan

Kull: Exile of Atlantis

The Best of Robert E. Howard

Volume 1: Crimson Shadows

The Best of Robert E. Howard

Volume 2: Grim Lands

The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume Two, is a work of fiction.

Names, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s

imagination or are used fictitiously.

A Del Rey Trade Paperback Original

Copyright © 2007 by Robert E. Howard Properties, LLC

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Del Rey Books,

an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

DEL REY is a registered trademark and the Del Rey colophon

is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

The stories and related names, logos, characters, and distinctive likenesses herein may be trademarks or registered trademarks of Conan Properties International LLC, Kull Productions, Inc., Solomon Kane, Inc., or Robert E. Howard Properties, LLC.

This edition published by arrangement with Robert E. Howard Properties, LLC

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Howard, Robert Ervin, 1906–1936.

The best of Robert E. Howard; illustrated by Jim & Ruth Keegan.

p. cm.

“A Del Rey trade paperback original.”

eISBN: 978-0-345-50250-6

I. Title.

PS3515.O842A6 2007

813′.52 – dc22 2007029740

www.delreybooks.com

v3.1

To Marcelo Anciano

Without whom …

Jim & Ruth Keegan

By This Axe I Rule!

first published in King Kull, 1967

The King and the Oak

first published in Weird Tales, February 1939

The Mirrors of Tuzun Thune

first published in Weird Tales, September 1929

The Tower of the Elephant

first published in Weird Tales, March 1933

Which Will Scarcely Be Understood

first published in Weird Tales, October 1937

Wings in the Night

first published in Weird Tales, July 1932

Solomon Kane’s Homecoming

first published in Fanciful Tales, Fall 1936

Lord of Samarcand

first published in Oriental Stories, Spring 1932

Timur-Lang

first published in The Howard Collector, Summer 1964

A Song of the Naked Lands

first published in A Song of the Naked Lands, 1973

The Shadow of the Vulture

first published in The Magic Carpet Magazine, January 1934

Echoes from an Anvil

first published in Verses in Ebony, 1975

The Bull Dog Breed

first published in Fight Stories, February 1930

Black Harps in the Hills

first published in Omniumgathum, 1976

The Man on the Ground

first published in Weird Tales, July 1933

Old Garfield’s Heart

first published in Weird Tales, December 1933

Vultures of Wahpeton

first published in Smashing Novels, December 1936 (as “Vultures of Whapeton”)

Gents on the Lynch

first published in Argosy, October 17, 1936

The Grim Land

first published in The Grim Land and Others, 1976

Pigeons from Hell

first published in Weird Tales, May 1938

Never Beyond the Beast

first published in The Ghost Ocean, 1982

Wild Water

first published in Cross Plains, September 1975

Musings

first published in Witchcraft & Sorcery, January – February 1971

Son of the White Wolf

first published in Thrilling Adventures, December 1936

Black Vulmea’s Vengeance

first published in Golden Fleece, November 1938

Flint’s Passing

first published in Fantasy Crossroads, May 1975

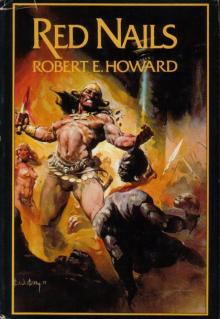

Red Nails

first published in Weird Tales, July, August – September, October 1936

Cimmeria

first published in The Howard Collector, Winter 1965

Contents

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Foreword

Introduction

By This Axe I Rule!

The King and the Oak

The Mirrors of Tuzun Thune

The Tower of the Elephant

Which Will Scarcely Be Understood

Wings in the Night

Solomon Kane’s Homecoming

Lord of Samarcand

Timur-Lang

A Song of the Naked Lands

The Shadow of the Vulture

Echoes from an Anvil

The Bull Dog Breed

Black Harps in the Hills

The Man on the Ground

Old Garfield’s Heart

Vultures of Wahpeton

Gents on the Lynch

The Grim Land

Pigeons from Hell

Never Beyond the Beast

Wild Water

Musings

Son of the White Wolf

Black Vulmea’s Vengeance

Flint’s Passing

Red Nails

Cimmeria

Appendices

Barbarian at the Pantheon-Gates

Notes on the Original Howard Texts

Sketchbook

Foreword

The first time we saw the layouts and illustrations for The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane, we couldn’t believe our eyes. Here was an illustrated book of a variety that no one had tried to produce in decades. It was magnificent. In fact, it was difficult to imagine such a book actually being published in a world that didn’t take the time for such things any longer.

Little did we realize that ten years later, that book would have become the first volume in an ongoing illustrated library collecting the works of Robert E. Howard, and that we would find ourselves illustrating the seventh and eighth volumes in that series.

And what a treat it’s been.

Every paragraph of Howard’s vivid prose has something that fires the artistic imagination. Pirates and knights. Cowboys and barbarians. Warrior women and monsters. Is there an artist alive who can resist such things?

The stories of Robert E. Howard challenge your inner kid – illustrator and reader alike – to come out and play, and stay out past dinner time.

Enjoy.

Jim & Ruth Keegan

Studio City, California

July 2007

Introduction

The “call to adventure” … signifies that destiny has summoned the hero and transferred his spiritual center of gravity from within the pale of his society to a zone unknown. This fateful region of both treasure and danger may be variously represented: as a distant land, a forest, a kingdom underground, beneath the waves, or above the sky, a secret island, lofty mountaintop, or profound dream state; but it is always a place of strangely fluid and polymorphous beings, unimaginable torments,

superhuman deeds, and impossible delight.

–Joseph Campbell

No writer has ever answered the call to adventure with greater alacrity than Robert E. Howard, and few have proven superior to him in issuing that call to readers. For all that his stories appeared in the pages of pulp magazines during the era between the World Wars, they are always fresh, always modern, “always ready,” as David Weber observes, “to teach another generation of writers how to tell the high, old tales of doom and glory,” because they spring from that eternal well of hero tales from which the most enduring writers have drawn. His is the art of the bard, the skald, the cyfarwydd, the seanchai, the griot, the hakawaty, the biwa hoshi. Howard, in fact, may be said to have a direct connection to the oral tradition, as he is well attested to have talked his stories out, sometimes at the top of his voice, while he was writing, and to have been a spellbinding oral yarnspinner among his friends. The tales in this book, and in its companion volume, could well have been told around a fire, the audience listening raptly to the teller, surrounded, just outside the circle of light, by Mystery, and Adventure.

The telling of stories is as old as mankind, and many theorists believe that stories do much more than simply entertain us (though of course there’s nothing wrong with that). They help us find a way to make sense of the world and our lives, to give a narrative structure of meaning to what might otherwise seem a chaotic jumble of events. (In a startlingly postmodernist metanarrative within his loosely autobiographical novel, Post Oaks & Sand Roughs, written in 1928, Howard critiqued the very book he, and through him his fictional self, was in the act of writing: “It was too vague, too disconnected, too full of unexplained and trivial incidents – too much like life in a word.”) Story helps us connect and explain the incidents of life, helps us understand who we are and where we are and how we are to behave in the world and our society.

Among the oldest and most popular types of stories are hero tales, centered around an individual who performs some notable deed, and in so doing demonstrates some type of exemplary behavior (or, alternatively, behaves in a way that brings about his comeuppance, thereby showing us how not to act). It is this type of story that most appealed to Robert E. Howard, and in this volume and its companion you will find many fine examples. They can be, and all too frequently have been, read superficially, as amusements to while away the idle hour. They work splendidly on that level, and as Joseph Campbell noted, “The storyteller fails or succeeds in proportion to the amusement he affords.” For those who enjoy a fast-paced narrative expressed in direct yet poetic language, Howard succeeds marvelously. But in the best stories, there is more than amusement. “The function of the craft of the tale,” says Campbell, “was not simply to fill the vacant hour but to fill it with symbolic fare.” And here, too, Howard succeeds wonderfully. One of the real secrets of his enduring appeal, I think, is that he worked with archetypal materials almost directly, delving deeply into the reservoir of myth and dream to bring forth undisguised images and themes, to free them from the flowery conventions of “romance” that had accreted to them over the centuries, and to present them couched in language and in a worldview that was distinctly modern.

As Don Herron observed, at the same time Dashiell Hammett and the “hard-boiled” writers of Black Mask were dragging the mystery story out of the drawing rooms of the upper classes and onto the “mean streets” of the lower, Howard was hauling fantasy from the castles and magical forests to which it had long been relegated into a grimmer, darker world that was not so far removed from the experience of postwar readers. His heroes are not always “good guys”: they may be thieves, pirates, gunmen, feudists, outcasts guilty of terrible crimes. But they are good men, who adhere to strict inner codes of morality even when doing so conflicts with their self-interest. They match Raymond Chandler’s famous description of the hard-boiled private eye: “a man … who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid … a complete man and a common man and yet an unusual man … a man of honor, by instinct, by inevitability, without thought of it, and certainly without saying it … the best man in his world and a good enough man for any world … The story is this man’s adventure in search of a hidden truth, and it would be no adventure if it did not happen to a man fit for adventure. He has a range of awareness that startles you, but it belongs to him by right, because it belongs to the world he lives in.” Says Herron, “Many critics have taken up the cause of Hammett and the Black Mask writers, arguing for the ‘moral vision’ in their work, but most … have missed similar themes in [Howard’s] writing.”

It is not within the scope of this introduction to examine the themes and imagery of Howard’s tales: Steven Tompkins, in this volume, and Charles Hoffman, in its companion, have done an outstanding job of indicating something of the richness to be found in Howard’s work, and there is a growing body of critical literature for those who are so inclined. Read simply for pleasure, or plumbed for the richness of its symbolic content and ideas, the work of Robert E. Howard will reward the reader on multiple levels.

As I noted in the introduction to the first volume, this is largely my personal selection of the stories and poems of Robert E. Howard that I think are his best. However, I was greatly aided by a poll I conducted among longtime Howard enthusiasts and scholars, and I have sought the advice of colleagues when I faced tough choices. To keep the books manageable, we’ve had to leave out some outstanding tales and verse, of course, and many Howard fans will undoubtedly find some of their favorites missing, as are some of my own. I do hope that, should the stories or poems in this book pique your interest, you will seek out other collections: the excellent website Howard Works (www.howardworks.com) is the best online bibliographical resource.

Many of Howard’s contemporaries in the weird fiction field agreed with H. P. Lovecraft that “the King Kull series probably forms a weird peak” to his work, remarkable considering that only three tales featuring Kull saw publication during Howard’s lifetime. Two of these (The Shadow Kingdom and Kings of the Night, the latter generally considered a Bran Mak Morn story in which Kull is a guest character) were included in our first volume; the other, The Mirrors of Tuzun Thune, is presented here. It is a metaphysical reverie that almost amounts to a prose poem, and certainly leads one to wonder how some critics ever got the idea that Howard’s barbarian characters were all brawn and no brains.

Unpublished during Howard’s life, but among the finest of his Kull tales, was By This Axe I Rule! The story is not, strictly speaking, one of “swords and sorcery” – there is no fantasy element other than the setting itself. In this tale, the ostensible villains are the conspirators who hope to overthrow Kull, but I think the real villain is one more terrible than any other-worldly demon, nefarious sorcerer, or would-be assassins: it is the stultifying traditions and laws of an ancient society, inflexible rules that stifle and inhibit everyone, from king to servant. The lack of a fantasy element made the story unsuitable for Howard’s primary market at the time, Weird Tales, while the imaginary antediluvian setting probably hurt it with the non-fantasy magazines to which he submitted it. A few years later Howard would rework the story considerably, turning it into the first of the Conan of Cimmeria tales, The Phoenix on the Sword. While the rewritten story was quite good, I’m not the only one who finds the Kull version superior: in my informal survey it outpolled the Conan version by almost three to one.

Conan, of course, proved to be a far more popular character with the readers, from the original Weird Tales appearances to the present day. This has been something of a mixed blessing: on the one hand, millions of people have become familiar with the character through comics, movies, role-playing games and other popular media, to the point that, like Sherlock Holmes, Dracula, and Tarzan, the character is more widely known than his creator; on the other hand, though, many of those millions know the character only through the adaptations into other media, and the popular image of the fur-clad, muscle-bound, inarticulate barbarian is far from How

ard’s original conception. In The Tower of the Elephant, one of the earliest written of the series, a youthful Conan, not long out of the Cimmerian hills, finds himself derided as an outlandish heathen, but soon encounters one far more outlandish than himself. Anyone who thinks Conan is little more than a brute will find those preconceptions shattered in this tale of compassion, and of unearthly revenge.

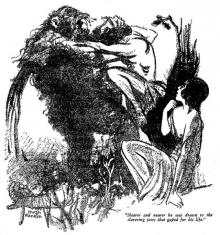

The first of Howard’s numerous series heroes to see publication was Solomon Kane, a somber Puritan adventurer and self-appointed redresser of wrongs. Believing himself to be acting as an instrument of God’s will, Kane nevertheless, in occasional moments of self-awareness, recognizes that he is prompted as much by lust for adventure as by love of God. A rigid Puritan in his creed, he nonetheless consorts with a tribal shaman and carries a ju-ju staff given him by that worthy. Wings in the Night is one of the Kane stories set in Darkest Africa, that continent that so fired the imaginations of writers like Rider Haggard and Howard, and that largely existed only in the imagination. The “white-skinned conqueror” business at the end makes us rather uncomfortable today, but as Patrick Burger notes, “Solomon Kane is all about contradictions,” and the text itself subverts one reading with another: the Aryan fighting man, we note, is standing with his ju-ju stave in one hand; the ardent Puritan who thanks the Lord for bringing him through was earlier the gibbering madman who “cursed the gods and devils who make mankind their sport, and he cursed Man who lives blindly on and blindly offers his back to the iron-hoofed feet of his gods.” Kane is one of the most complex and fascinating characters in fantasy literature.

“There is no literary work, to me, half as zestful as rewriting history in the guise of fiction,” Howard wrote to Lovecraft, so when Farnsworth Wright, editor of Weird Tales, wrote him that he planned to start a new magazine of Oriental tales, and “especially want[ed] historical tales – tales of the Crusades, of Genghis Khan, of Tamerlane, and the wars between Islam and Hindooism,” Howard was excited enough to cut short a vacation trip with some friends and return to Cross Plains and start working to fill the order. He produced some of his very best work for that unfortunately shortlived magazine, first called Oriental Stories and then The Magic Carpet Magazine. We present two of them here, Lord of Samarcand and The Shadow of the Vulture, and we wish we could include more: in my opinion, these stories represent Howard at the very top of his game. In addition to these two, I would encourage readers to seek out The Lion of Tiberias, The Sowers of the Thunder, and Hawks of Outremer, in particular. The protagonists of these stories are flawed human beings, at times bordering on the psychopathic, and they fight for causes no more noble than they are. Howard has sometimes been taken to task for what some perceive as glorification of violence, but in these stories – and in the vast majority of his stories generally – there is no glory to be found in conflict, only dust and ashes. Of Lord of Samarcand he wrote, “There isn’t a gleam of hope in it. It’s the fiercest and most sombre thing I ever tried to write. A lot of milksops – maybe – will say it’s too savage to be realistic, but to my mind, it’s about the most realistic thing I ever attempted. But it’s the sort of thing I like to write – no plot construction, no hero or heroine, no climax in the accepted sense of the word, all the characters complete scoundrels, and every-body double-crossing everybody else.”

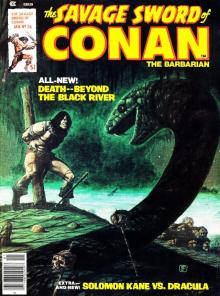

Beyond the Black River

Beyond the Black River Gods of the North

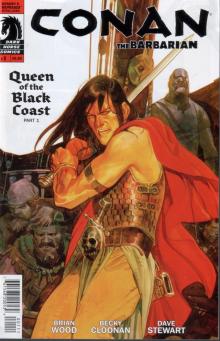

Gods of the North Queen of the Black Coast

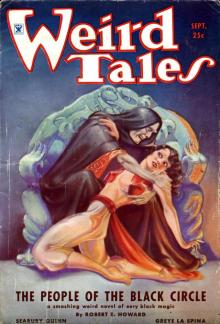

Queen of the Black Coast The People of the Black Circle

The People of the Black Circle Red Nails

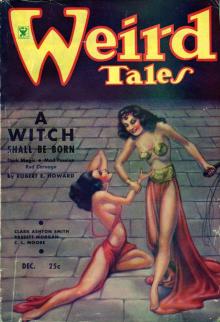

Red Nails A Witch Shall Be Born

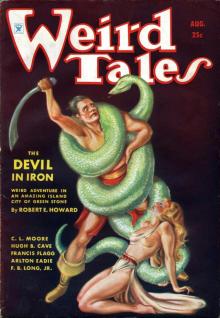

A Witch Shall Be Born The Devil in Iron

The Devil in Iron The Weird Tales of Conan the Barbarian

The Weird Tales of Conan the Barbarian The Bloody Crown of Conan

The Bloody Crown of Conan The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard

The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard Conan the Conqueror

Conan the Conqueror Conan the Barbarian

Conan the Barbarian Shadows in the Moonlight

Shadows in the Moonlight The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane

The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane Bran Mak Morn: The Last King

Bran Mak Morn: The Last King The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume One: Crimson Shadows

The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume One: Crimson Shadows The Best of Robert E. Howard: Crimson Shadows (Volume 1)

The Best of Robert E. Howard: Crimson Shadows (Volume 1) Black Hounds of Death

Black Hounds of Death Jewels of Gwahlur

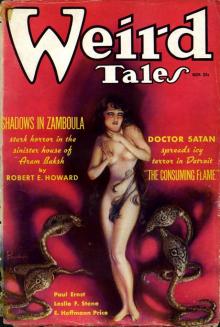

Jewels of Gwahlur Shadows in Zamboula

Shadows in Zamboula The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian

The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian The Mythos Tales

The Mythos Tales The Hour of the Dragon

The Hour of the Dragon The Hyborian Age

The Hyborian Age El Borak and Other Desert Adventures

El Borak and Other Desert Adventures The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1 The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1

The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1 The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1 El Borak: The Complete Tales

El Borak: The Complete Tales Kull: Exile of Atlantis

Kull: Exile of Atlantis The Conquering Sword of Conan

The Conquering Sword of Conan The Conan Compendium

The Conan Compendium The Conan Chronicles: Volume 1: The People of the Black Circle

The Conan Chronicles: Volume 1: The People of the Black Circle The Complete Chronicles of Conan: Centenary Edition

The Complete Chronicles of Conan: Centenary Edition Tales of Bran Mak Morn (Serapis Classics)

Tales of Bran Mak Morn (Serapis Classics) Delphi Works of Robert E. Howard (Illustrated) (Series Four)

Delphi Works of Robert E. Howard (Illustrated) (Series Four) Conan the Barbarian: The Stories That Inspired the Movie

Conan the Barbarian: The Stories That Inspired the Movie People of the Dark Robert Ervin Howard

People of the Dark Robert Ervin Howard Grim Lands

Grim Lands Wings in the Night

Wings in the Night Gardens of Fear

Gardens of Fear A Thunder of Trumpets

A Thunder of Trumpets Detective of the Occult

Detective of the Occult Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures

Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures Historical Adventures

Historical Adventures Moon of Skulls

Moon of Skulls The Robert E. Howard Omnibus: 97 Collected Stories

The Robert E. Howard Omnibus: 97 Collected Stories The Pirate Story Megapack: 25 Classic and Modern Tales

The Pirate Story Megapack: 25 Classic and Modern Tales The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 2

The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 2 The Conan Chronicles, Vol. 1: The People of the Black Circle

The Conan Chronicles, Vol. 1: The People of the Black Circle Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures M

Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures M The Complete Chronicles of Conan

The Complete Chronicles of Conan Conan the Barbarian: The Chronicles of Conan (collected short stories)

Conan the Barbarian: The Chronicles of Conan (collected short stories) The Conan the Barbarian Stories

The Conan the Barbarian Stories The Best Horror Stories of

The Best Horror Stories of Tigers Of The Sea cma-4

Tigers Of The Sea cma-4 The Hours of the Dragon

The Hours of the Dragon Conan the Cimmerian: The Complete Tales (Trilogus Classics)

Conan the Cimmerian: The Complete Tales (Trilogus Classics) Collected Western Stories of Robert E. Howard (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics)

Collected Western Stories of Robert E. Howard (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics) The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 1

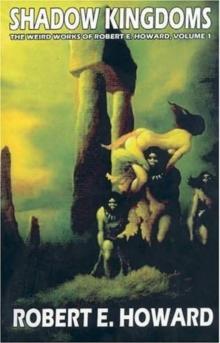

The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 1 Shadow Kingdoms

Shadow Kingdoms