- Home

- Robert E. Howard

Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures Page 4

Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures Read online

Page 4

She forced a laugh. “He was drunk.”

Broder burst into wild curses as the violent passion of the Viking surged up in him.

“You lie, you wanton!” he grated, seizing her white wrist in an iron grip. “You were born to lure men to their doom! But you cannot play fast and loose with Broder of Man!”

“You are mad!” she cried, twisting vainly in his grasp. “Release me or I will call my guards!”

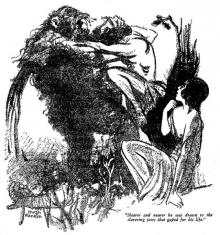

“Call them!” he snarled. “And I will slash the heads from their bodies. Cross me now and blood shall run ankle-deep in Dublin’s streets. By Thor, there will be no city left for Brian to burn! Mailmora, Sitric, Sigurd, Amlaff – I will cut all their throats and drag you naked to my longship by your yellow hair! Now dare to call out!”

And she dared not. He forced her to her knees, twisting her white arm brutally till she bit her lip to keep from screaming.

“Confess!” he snarled. “You promised Sigurd the same thing you promised me, knowing neither of us would throw away his life for less.”

“No! – no! – no!” she shrieked. “I swear by the ring of Thor – ” then as the agony grew unbearable she cried out: “Yes! – yes! – I promised him – let me go – oh, let me go!”

“So!” the Viking tossed her contemptuously onto a pile of silken cushions where she lay whimpering and disheveled.

“You promised me and you promised Sigurd,” said he, looming darkly above her, “but the promise you made me, you will keep – else you had better never been born. The throne of Ireland is a small thing beside my desire for you – if I cannot have you, no one shall.”

“But what of Sigurd?”

“He will fall in battle – or afterwards,” he answered grimly.

“Good enough!” Dire indeed was the extremity in which Kormlada did not have her wits about her. “It is you I love, Broder; I only promised him because he would not aid us otherwise – ”

“Love!” the grim Viking laughed bitterly. “You love Kormlada – no one else. I understand you; but you will keep your vow to me or you will rue it.” And turning on his heel, he strode from her chamber.

Kormlada rose, rubbing her arm where the blue marks of his savage fingers marred her white skin.

“May he fall in the first onset,” she said between her teeth. “If either survive may it be that tall fool, Sigurd – methinks he would be a husband more easily managed than that black-haired savage. I will perforce marry him if he survives the battle, but by the ring of Thor, he shall not long press the throne of Ireland – I will send him to join Brian – ”

“You speak as if King Brian were already dead,” a silvery mocking voice brought Kormlada about suddenly to face the other person in the world she feared besides Broder. Her eyes widened as from behind a satin hanging stepped a small dark girl clad in shimmering green.

“Eevin!” Kormlada gasped, recoiling. “Stand back – cast no spell on me, little witch – ”

“Who am I to bewitch the great queen who has bewitched so many men?” asked Eevin mockingly, secure in the knowledge of the queen’s superstitious fears; to the Danish woman the Pictish girl was something fearsome and unhuman – an uncanny sprite of the deep woods.

“How came you in my palace?” demanded Kormlada with a weak effort at imperiousness.

“How came the breeze through the trees?” answered the forest girl. “Your guards watched well enough, but do the oxen know when the field mice run through the wheat? You of the fair folk are like blind men and deaf when the dark people steal among you.”

“Why do you spy on me?” asked the queen angrily.

“To see what the great Gormlaith does when a Viking manhandles her in her own chamber,” taunted Eevin. “So many men have knelt before Gormlaith, it was right merry to see Gormlaith on her knees before Broder.”

At this heckling the Danish queen went white, clenching her hands until the nails bit into the delicate palms and brought trickles of blood.

“I will have you thrown into a dungeon for the rats to eat, you witch!” she whispered, so choked with fury she could not speak louder.

Eevin’s dainty lip curled with contempt.

“You dare not touch me; you fear I might put on you a spell to rob you of that cruel beauty whereby you rule men. Now tell me, quickly: what was it Broder told you before I came into this chamber?”

“He had been consulting the oracle of the sea-people,” Kormlada answered sullenly.

“The blood and the torn heart?” Eevin’s lips writhed with disgust. “Faugh! You Danars are but bloody beasts! What did it portend?”

“The priest bade Broder attack tomorrow,” answered the queen, not considering, with the usual illogic of the primitive, that if, as she believed, Eevin were indeed a witch, she should know without asking.

Eevin stood with bent head for a moment, then turned and, slipping through the hangings, vanished from Kormlada’s sight. The proud queen, who in the last few minutes had been bullied and humiliated for the first time in her cruel life, turned like an angry pantheress and left the chamber in a brooding rage that promised little good for anyone who had dealings with her.

Alone in his tent with the heavily armed gallaglachs ranged outside, King Brian woke suddenly from a fitful and unquiet sleep. The thick torches which burned without illumined the interior of his tent and in their light he saw a small childish figure.

“Eevin!” he sat up, half startled, half provoked. “By my soul, child, well for kings that your people take no part in the intrigues of the conquering folk, when you can steal under the very noses of the guards into a guarded tent. Do you seek Dunlang?”

The Pictish girl shook her head sadly. “I see him no more alive, great king. Were I to go to him now, my own black sorrow might unman him. I will come to him among the dead tomorrow.”

King Brian involuntarily shivered.

“But it is not of my woes that I came to speak, great king,” the girl continued wearily. “It is not the way of the forest folk to mix in the quarrels of the fair folk – but I love a fair man. This night I was in Sitric’s castle and talked with Gormlaith.”

King Brian winced at the name of his divorced queen, but spoke steadily: “And your news?”

“Broder strikes on the morrow.”

The king shook his head heavily.

“I am a true Christian, I trust, and it vexes my soul to spill blood on the Holy Day. But if God wills it, we will not await their onslaught, but will march at dawn to meet them. I will send a swift runner to bring back Donagh and his band – ”

Again Eevin shook her head.

“Nay, great king. Let Donagh live; after the great battle the Dalcassians will need strong arms to brace the sceptre.”

Brian gazed fixedly at her for an instant. “I read my own doom in those words, little witch-girl of the woods; have you cast my fate?”

Eevin spread her hands helplessly. “My lord, Gormlaith the pagan believes me to be a sorceress, breathing spells and black dooms. You are wise and know otherwise, yet even you look on me as a person uncanny. I cannot rend the Veil at will; I know neither spells nor sorcery; not in smoke nor blood have I read it, but a weird has come upon me and I see – vaguely – through flame and the dim clash of battle – ”

“And I shall fall?”

She bowed her face in her hands. “It is written.”

“Well, let it fall as God wills,” said King Brian tranquilly. “I have lived long and deeply. Weep not, little girl of the forest; through the darkest mists of gloom and night, dawn yet rises on the world. My clan shall reverence you in the long days to come. And go now, for the night wanes toward morn and I would make my peace with God.”

And Eevin of Craglea went like a shadow from the tent of the king.

V

THE FEASTING OF THE EAGLES

Through the mist of the white dawn men moved like ghosts and weapons clanked eerily. Conn stretched his muscular arms, yawned cavernously and loosened his great blade in its sheath.

“This is the day the ravens drink blood, my lord,” he grinned, and Dunlang O’Hartigan nodded absently.

“Come hither and aid me to don this cursed cage,” said the young Dalcassian. “For Eevin’s sake I will wear it, but I had rather go into battle stark naked, by the saints!”

The Gaels were on the move, marching from Kilmainham in the same formation in which they intended to enter the battle. First came the Dalcassians, big rangy men in their saffron tunics, with a round buckler of steel-braced yew wood on the left arm and the right hand gripping the dreaded Dalcassian axe against which no armor could stand. This axe differed greatly from the heavy two-handed weapon of the Danes; the Irish wielded it with one hand, the thumb stretched along the haft to guide the blow, and they had attained a skill at axe-fighting never before or since equalled. Hauberks they had none, neither the gallaglachs nor the kerns, though some of their chiefs, like Murrogh, wore light steel caps. But the tunics of warrior and chief alike had been woven with such skill and steeped in vinegar until their remarkable toughness afforded some protection against sword and arrow.

At the head of the Dalcassians strode Prince Murrogh, his fierce eyes alight, smiling as though he went to a feast instead of a slaughtering. On one side went Dunlang O’Hartigan in his Roman corselet, and on the other side the two Turloghs – the son of Murrogh, and Turlogh Dubh, who alone of all the Dalcassians, always went into battle fully armored. He looked grim enough, despite his youth, with his dark face and smoldering blue eyes, clad as he was in a full shirt of black mail, mail leggings and a steel helmet with a mail drop, and bearing a spiked buckler. Unlike the rest of the chiefs who preferred their swords in battle, Turlogh Dubh fought with an axe he himself had forged and of all the Gaels, none could match him at axe-fighting. So these chiefs led the warriors of Clare to the slaughter and behind Dunlang came Conn, bearing the Roman helmet.

Close behind the Dalcassians were the two companies of the Scotch with their chiefs, the Stewards of Scotland, Lennox and Donald of Mar, who, long skilled in war with the Saxons, wore helmets with horse-hair crests, and coats of mail. With them came the men of South Munster commanded by Prince Meathla O’Faelan.

The third division consisted of the warriors of Connacht, wild men of the west, shock-headed and ferocious, naked but for their wolf-skins, with their chiefs O’Kelly and O’Hyne. And O’Kelly marched as a man whose soul is heavy within him, for the shadow of his meeting with King Malachi the night before fell gauntly across him.

A little apart from the three main divisions marched the kerns and gallaglachs of Meath, their king riding slowly before them.

And before all the host rode King Brian Boru on a snow white steed, his white locks blown about his ancient face and his eyes strange and fey, so that the wild kerns gazed upon him with superstitious awe. And so the Gaels came before Dublin.

And there they saw the hosts of Lochlann and of Leinster drawn up in full battle array, stretching in a wide crescent from Dubhgall’s Bridge to the narrow river Tolka which cuts the plain of Clontarf. Three main divisions there were – the foreign Northmen, the Vikings, with Sigurd and the grim Broder; and flanking them on the one side the fierce Danes of Dublin under their chief, a sombre wanderer whose name no man knew, but who was called by the general name of his race – Dubhgall, The Dark Stranger; and on the other flank the Irish of Leinster with their king Mailmora, brother to Kormlada. The Danish fortress on the hill beyond the Liffey river bristled with armed men where King Sitric guarded the city.

There was but one way into the city from the north – the direction from which the Gaels were advancing – for in those days Dublin lay wholly south of the Liffey: that was the bridge called Dubhgall’s Bridge. The Danes stood with one horn of their line guarding this entrance, their ranks curving out toward the Tolka, their backs to the sea. The Gaels advanced along the level plain which stretched between Tomar’s Wood and the shore.

With scarce a bow-shot separating the hosts, the Gaels halted and King Brian rode in front of them, holding high a crucifix.

“Sons of Goidhel!” he called in a voice that rang like a trumpet call. “It is not given me to lead you into the fray, as I led you in the days of old. But I have pitched my tent behind your lines, where you must trample me if you flee. You will not flee! Remember a hundred years of outrage and infamy! Remember your burning houses, your slaughtered kin, your ravished women, your babes enslaved! Before you stand your oppressors! On this day our good Lord died for you! There stand the heathen hordes which revile His Name and slay His people! I have but one command to give – Conquer or die!”

The wild hordes yelled like wolves and a forest of axes brandished on high. King Brian bowed his head and his face was suddenly grey.

“Let them lead me back to my tent,” he whispered to Murrogh. “Age has withered me from the play of the axes and my doom is hard upon me. Go forth and may God stiffen your arms to the slaying!”

Now as the king rode slowly back to his tent among his guardsmen, there was a tightening of girdles, a drawing of blades, a dressing of shields. Conn placed the Roman helmet on the head of Dunlang and grinned at the result; thus cased the young chief looked like some mythical iron monster out of Norse legendry. And now the hosts moved inexorably toward each other.

The Vikings had assumed their favorite wedge-shaped formation with Sigurd and Broder with their thousand iron-clad slayers at the tip. The Northmen offered a strong contrast to the loose lines of half-naked Gaels. They moved in compact ranks, armored with horned helmets, heavy scale-mail coats reaching to their knees, and leggings of seasoned wolf-hide braced with iron plates, and bearing great kite-shaped shields of linden-wood with iron rims, and long spears. The thousand warriors in the forefront wore not only heavy hauberks, but long leggings and gauntlets of mail also, so that from crown to heel they were armored. These marched in a solid shield-wall, bucklers overlapping, and over their iron ranks floated the grim raven banner which legend said always brought victory to Sigurd but death to the bearer. Now it was borne by old Rane Asgrimm’s son who felt that the hour of his death was at hand anyway.

At the tip of the wedge, like the point of a spear, were the champions of Lochlann – Broder in his dully glittering blue mail which no blade had ever dinted; Jarl Sigurd, tall, blond-bearded, gleaming in his golden-scaled hauberk; Hrafn the Red, in whose soul lurked a mocking devil that moved him to gargantuan laughter, even in the madness of battle; the comrades Thorstein and Asmund, tall, fierce chiefs; Prince Amlaff, roving son of the king of Norway; Platt of Danemark; Jarl Thorwald Raven of the Hebrides; Anrad the berserk.

Toward this formidable array the Irish advanced at quick pace in more or less open formation and with scant attempt at orderly ranks. But Malachi and his warriors wheeled suddenly and drew off to the extreme left, taking up their position on the high ground by Cabra. And when Murrogh saw this he cursed beneath his breath and Black Turlogh growled: “Who said an O’Neill forgets an old grudge? By Crom, Murrogh, we may have to guard our backs as well as our breasts, before this fight be won!”

Now suddenly from the Viking ranks strode Platt of Danemark whose red hair floated like a crimson veil about his bare head. The hosts watched eagerly, for in those days few battles began without preliminary single combats.

“Donald!” shouted Platt, his blue eyes blazing with a reckless mirth, flinging up his naked sword so that the rising sun caught it with a sheen of silver. “Where is Donald of Mar? Are you there, Donald, as you were at Rhu Stoir, or do you skulk from the fray?”

“I am here, rogue!” answered the Scotch chief as he strode, tall, gaunt and sombre from among his men, flinging away his scabbard. Highlander and Dane met in the middle space between the hosts, Donald wary as a hunting wolf, Platt leaping in, reckless and head-long, his eyes alight and dancing with a kind of laughing madness. Yet it was the wary Steward’s foot which slipped suddenly on a rolling pebble, and before he could regain his balance, Platt’s sword lunged into him so fiercely the ke

en point tore through the scales of his corselet and sank deep beneath his heart. Platt yelled in mad exultation and the shout broke in a sudden gasp. Even as he crumpled Donald of Mar lashed out with a dying stroke that split the Dane’s head and the two fell together.

Thereat a deep-toned roar went up to the heavens and the two great hosts rolled together like a vast wave.

And then were struck the first blows of a battle such as the world was never to see again. Here were no maneuvers of strategy, no charges of cavalry, no flight of arrows. There forty thousand men fought on foot, hand to hand, man to man, slaying and dying in one mad red chaos. The issue was greater than to decide whether Dane or Gael should rule Ireland; it was Christian against heathen; Jehovah against Odin; it was the last combined onslaught of the Norse races against the world they had looted for three hundred years. It was more; it was the titanic death-throes of a passing epoch – the twilight of a fading age. For on the field of Clontarf the death-knell of the Vikings was struck and Ireland won her last great national victory. Darkness lay behind and before the age of Brian Boru and Clontarf, which was but a brief age of light, swiftly fading into the gloom of anarchy and civil discord that culminated in the coming of the Norman conquerors.

But the men who fought at Clontarf guessed none of this. Red battle broke in howling waves about their spears and they had no time for dreams and prophesies.

The first to shock were the Dalcassians and the Vikings and as they met both lines rocked at the impact. The deep-throated roar of the Norsemen mingled with the wild yells of the Gaels and the Northern spears splintered among the Western axes. Foremost in the fray was Murrogh, his great body leaping and straining as he roared and smote. In each hand he bore a heavy sword and smiting right and left he mowed men down like corn, for neither shield nor helmet stood beneath his terrible blows. And behind him came his warriors slashing and howling like devils.

Beyond the Black River

Beyond the Black River Gods of the North

Gods of the North Queen of the Black Coast

Queen of the Black Coast The People of the Black Circle

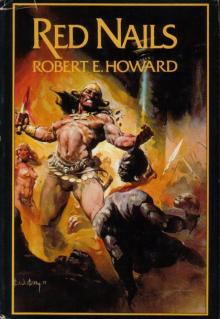

The People of the Black Circle Red Nails

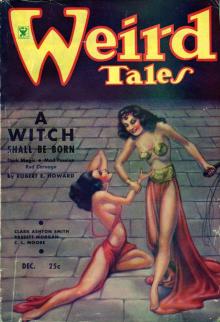

Red Nails A Witch Shall Be Born

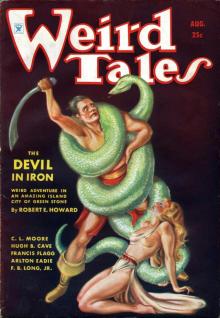

A Witch Shall Be Born The Devil in Iron

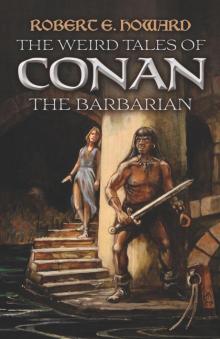

The Devil in Iron The Weird Tales of Conan the Barbarian

The Weird Tales of Conan the Barbarian The Bloody Crown of Conan

The Bloody Crown of Conan The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard

The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard Conan the Conqueror

Conan the Conqueror Conan the Barbarian

Conan the Barbarian Shadows in the Moonlight

Shadows in the Moonlight The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane

The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane Bran Mak Morn: The Last King

Bran Mak Morn: The Last King The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume One: Crimson Shadows

The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume One: Crimson Shadows The Best of Robert E. Howard: Crimson Shadows (Volume 1)

The Best of Robert E. Howard: Crimson Shadows (Volume 1) Black Hounds of Death

Black Hounds of Death Jewels of Gwahlur

Jewels of Gwahlur Shadows in Zamboula

Shadows in Zamboula The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian

The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian The Mythos Tales

The Mythos Tales The Hour of the Dragon

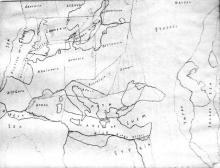

The Hour of the Dragon The Hyborian Age

The Hyborian Age El Borak and Other Desert Adventures

El Borak and Other Desert Adventures The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1 The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1

The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1 The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1 El Borak: The Complete Tales

El Borak: The Complete Tales Kull: Exile of Atlantis

Kull: Exile of Atlantis The Conquering Sword of Conan

The Conquering Sword of Conan The Conan Compendium

The Conan Compendium The Conan Chronicles: Volume 1: The People of the Black Circle

The Conan Chronicles: Volume 1: The People of the Black Circle The Complete Chronicles of Conan: Centenary Edition

The Complete Chronicles of Conan: Centenary Edition Tales of Bran Mak Morn (Serapis Classics)

Tales of Bran Mak Morn (Serapis Classics) Delphi Works of Robert E. Howard (Illustrated) (Series Four)

Delphi Works of Robert E. Howard (Illustrated) (Series Four) Conan the Barbarian: The Stories That Inspired the Movie

Conan the Barbarian: The Stories That Inspired the Movie People of the Dark Robert Ervin Howard

People of the Dark Robert Ervin Howard Grim Lands

Grim Lands Wings in the Night

Wings in the Night Gardens of Fear

Gardens of Fear A Thunder of Trumpets

A Thunder of Trumpets Detective of the Occult

Detective of the Occult Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures

Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures Historical Adventures

Historical Adventures Moon of Skulls

Moon of Skulls The Robert E. Howard Omnibus: 97 Collected Stories

The Robert E. Howard Omnibus: 97 Collected Stories The Pirate Story Megapack: 25 Classic and Modern Tales

The Pirate Story Megapack: 25 Classic and Modern Tales The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 2

The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 2 The Conan Chronicles, Vol. 1: The People of the Black Circle

The Conan Chronicles, Vol. 1: The People of the Black Circle Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures M

Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures M The Complete Chronicles of Conan

The Complete Chronicles of Conan Conan the Barbarian: The Chronicles of Conan (collected short stories)

Conan the Barbarian: The Chronicles of Conan (collected short stories) The Conan the Barbarian Stories

The Conan the Barbarian Stories The Best Horror Stories of

The Best Horror Stories of Tigers Of The Sea cma-4

Tigers Of The Sea cma-4 The Hours of the Dragon

The Hours of the Dragon Conan the Cimmerian: The Complete Tales (Trilogus Classics)

Conan the Cimmerian: The Complete Tales (Trilogus Classics) Collected Western Stories of Robert E. Howard (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics)

Collected Western Stories of Robert E. Howard (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics) The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 1

The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 1 Shadow Kingdoms

Shadow Kingdoms