- Home

- Robert E. Howard

Grim Lands Page 3

Grim Lands Read online

Page 3

“By Valka, they will remember this night, who strike the golden strings! The fall of the tyrant, the death of the despot – what songs I shall make!”

His eyes burned with a wild fanatical light and the others regarded him dubiously, all save Ascalante who bent his head to hide a grin. Then the outlaw rose suddenly.

“Enough! Get back to your places and not by word, deed or look do you betray what is in your minds.” He hesitated, eyeing Kaanuub. “Baron, your white face will betray you. If Kull comes to you and looks into your eyes with those icy grey eyes of his, you will collapse. Get you out to your country estate and wait until we send for you. Four are enough.”

Kaanuub almost collapsed then, from a reaction of joy; he left babbling incoherencies. The rest nodded to the outlaw and departed.

Ascalante stretched himself like a great cat and grinned. He called for a slave and one came, a somber evil looking fellow whose shoulders bore the scars of the brand that marks thieves.

“Tomorrow,” quoth Ascalante, taking the cup offered him, “I come into the open and let the people of Valusia feast their eyes upon me. For months now, ever since the Rebel Four summoned me from my mountains, I have been cooped in like a rat – living in the very heart of my enemies, hiding away from the light in the daytime, skulking masked through dark alleys and darker corridors at night. Yet I have accomplished what those rebellious lords could not. Working through them and through other agents, many of whom have never seen my face, I have honeycombed the empire with discontent and corruption. I have bribed and subverted officials, spread sedition among the people – in short, I, working in the shadows, have paved the downfall of the king who at the moment sits throned in the sun. Ah, my friend, I had almost forgotten that I was a statesman before I was an outlaw, until Kaanuub and Volmana sent for me.”

“You work with strange comrades,” said the slave.

“Weak men, but strong in their ways,” lazily answered the outlaw. “Volmana – a shrewd man, bold, audacious, with kin in high places – but poverty stricken, and his barren estates loaded with debts. Gromel – a ferocious beast, strong and brave as a lion, with considerable influence among the soldiers, but otherwise useless – lacking the necessary brains. Kaanuub, cunning in his low way and full of petty intrigue, but otherwise a fool and a coward – avaricious but possessed of immense wealth, which has been essential in my schemes. Ridondo, a mad poet, full of hare-brained schemes – brave but flighty. A prime favorite with the people because of his songs which tear out their heart-strings. He is our best bid for popularity, once we have achieved our design. I am the power that has welded these men, useless without me.”

“Who mounts the throne, then?”

“Kaanuub, of course – or so he thinks! He has a trace of royal blood in him – the old dynasty, the blood of that king whom Kull killed with his bare hands. A bad mistake of the present king. He knows there are men who still boast descent from the old dynasty but he lets them live. So Kaanuub plots for the throne. Volmana wishes to be reinstated in favor, as he was under the old regime, so that he may lift his estate and title to their former grandeur. Gromel hates Kelka, commander of the Red Slayers, and thinks he should have that position. He wishes to be commander of all Valusia’s armies. As to Ridondo – bah! I despise the man and admire him at the same time. He is your true idealist. He sees in Kull, an outlander and a barbarian, merely a rough footed, red handed savage who has come out of the sea to invade a peaceful and pleasant land. He already idolizes the king Kull slew, forgetting the rogue’s vile nature. He forgets the inhumanities under which the land groaned during his reign, and he is making the people forget. Already they sing ‘The Lament for the King’ in which Ridondo lauds the saintly villain and vilifies Kull as ‘that black hearted savage’ – Kull laughs at these songs and indulges Ridondo, but at the same time wonders why the people are turning against him.”

“But why does Ridondo hate Kull?”

“Because he is a poet, and poets always hate those in power, and turn to dead ages for relief in dreams. Ridondo is a flaming torch of idealism and he sees himself as a hero, a stainless knight, which he is, rising to overthrow the tyrant.”

“And you?”

Ascalante laughed and drained the goblet. “I have ideas of my own. Poets are dangerous things, because they believe what they sing – at the time. Well, I believe what I think. And I think Kaanuub will not hold the throne seat overlong. A few months ago I had lost all ambitions save to waste the villages and the caravans as long as I lived. Now, well – now we shall see.”

II

“THEN I WAS THE LIBERATOR – NOW –”

A room strangely barren in contrast to the rich tapestries on the walls and the deep carpets on the floor. A small writing table, behind which sat a man. This man would have stood out in a crowd of a million. It was not so much because of his unusual size, his height and great shoulders, though these features lent to the general effect. But his face, dark and immobile, held the gaze and his narrow grey eyes beat down the wills of the onlookers by their icy magnetism. Each movement he made, no matter how slight, betokened steel spring muscles and brain knit to those muscles with perfect coordination. There was nothing deliberate or measured about his motions – either he was perfectly at rest – still as a bronze statue, or else he was in motion, with that cat-like quickness which blurred the sight that tried to follow his movements. Now this man rested his chin on his fists, his elbows on the writing table, and gloomily eyed the man who stood before him. This man was occupied in his own affairs at the moment, for he was tightening the laces of his breast-plate. Moreover he was abstractedly whistling – a strange and unconventional performance, considering that he was in the presence of a king.

“Brule,” said the king, “this matter of statecraft wearies me as all the fighting I have done never did.”

“A part of the game, Kull,” answered Brule. “You are king – you must play the part.”

“I wish that I might ride with you to Grondar,” said Kull enviously. “It seems ages since I had a horse between my knees – but Tu says that affairs at home require my presence. Curse him!

“Months and months ago,” he continued with increasing gloom, getting no answer and speaking with freedom, “I overthrew the old dynasty and seized the throne of Valusia – of which I had dreamed ever since I was a boy in the land of my tribesmen. That was easy. Looking back now, over the long hard path I followed, all those days of toil, slaughter and tribulation seem like so many dreams. From a wild tribesman in Atlantis, I rose, passing through the galleys of Lemuria – a slave for two years at the oars – then an outlaw in the hills of Valusia – then a captive in her dungeons – a gladiator in her arenas – a soldier in her armies – a commander – a king!

“The trouble with me, Brule, I did not dream far enough. I always visualized merely the seizing of the throne – I did not look beyond. When king Borna lay dead beneath my feet, and I tore the crown from his gory head, I had reached the ultimate border of my dreams. From there, it has been a maze of illusions and mistakes. I prepared myself to seize the throne – not to hold it.

“When I overthrew Borna, then people hailed me wildly – then I was The Liberator – now they mutter and stare blackly behind my back – they spit at my shadow when they think I am not looking. They have put a statue of Borna, that dead swine, in the Temple of the Serpent and people go and wail before him, hailing him as a saintly monarch who was done to death by a red handed barbarian. When I led her armies to victory as a soldier, Valusia overlooked the fact that I was a foreigner – now she cannot forgive me.

“And now, in the Temple of the Serpent, there come to burn incense to Borna’s memory, men whom his executioners blinded and maimed, fathers whose sons died in his dungeons, husbands whose wives were dragged into his seraglio – Bah! Men are all fools.”

“Ridondo is largely responsible,” answered the Pict, drawing his sword belt up another notch. “He sings songs that make men mad.

Hang him in his jester’s garb to the highest tower in the city. Let him make rhymes for the vultures.”

Kull shook his lion head. “No, Brule, he is beyond my reach. A great poet is greater than any king. He hates me, yet I would have his friendship. His songs are mightier than my sceptre, for time and again he has near torn the heart from my breast when he chose to sing for me. I will die and be forgotten, his songs will live forever.”

The Pict shrugged his shoulders. “As you like; you are still king, and the people cannot dislodge you. The Red Slayers are yours to a man, and you have all Pictland behind you. We are barbarians, together, even if we have spent most of our lives in this land. I go, now. You have naught to fear save an attempt at assassination, which is no fear at all, considering the fact that you are guarded night and day by a squad of the Red Slayers.”

Kull lifted his hand in a gesture of farewell and the Pict clanked out the room.

Now another man wished his attention, reminding Kull that a king’s time was never his own.

This man was a young noble of the city, one Seno val Dor. This famous young swordsman and reprobate presented himself before the king with the plain evidence of much mental perturbation. His velvet cap was rumpled and as he dropped it to the floor when he kneeled, the plume drooped miserably. His gaudy clothing showed stains as if in his mental agony he had neglected his personal appearance for some time.

“King, lord king,” he said in tones of deep sincerity. “If the glorious record of my family means anything to your majesty, if my own fealty means anything, for Valka’s sake, grant my request.”

“Name it.”

“Lord king, I love a maiden – without her I cannot live. Without me, she must die. I cannot eat, I cannot sleep for thinking of her. Her beauty haunts me day and night – the radiant vision of her divine loveliness –”

Kull moved restlessly. He had never been a lover.

“Then in Valka’s name, marry her!”

“Ah,” cried the youth, “there’s the rub. She is a slave, Ala by name, belonging to one Volmana, count of Karaban. It is on the black books of Valusian law that a noble cannot marry a slave. It has always been so. I have moved high heaven and get only the same reply. ‘Noble and slave can never wed.’ It is fearful. They tell me that never in the history of the empire before has a nobleman wanted to marry a slave! What is that to me? I appeal to you as a last resort!”

“Will not this Volmana sell her?”

“He would, but that would hardly alter the case. She would still be a slave and a man cannot marry his own slave. Only as a wife I want her. Any other way would be hollow mockery. I want to show her to all the world, rigged out in the ermine and jewels of val Dor’s wife! But it cannot be, unless you can help me. She was born a slave, of a hundred generations of slaves, and slave she will be as long as she lives and her children after her. And as such she cannot marry a freeman.”

“Then go into slavery with her,” suggested Kull, eyeing the youth narrowly.

“This I desired,” answered Seno, so frankly that Kull instantly believed him. “I went to Volmana and said: ‘You have a slave whom I love; I wish to wed her. Take me, then, as your slave so that I may be ever near her.’ He refused with horror; he would sell me the girl, or give her to me but he would not consent to enslave me. And my father has sworn on the unbreakable oath to kill me if I should so degrade the name of val Dor as to go into slavery. No, lord king, only you can help us.”

Kull summoned Tu and laid the case before him. Tu, chief councillor, shook his head. “It is written in the great iron bound books, even as Seno has said. It has ever been the law, and it will always be the law. A noble may not mate with a slave.”

“Why may I not change that law?” queried Kull.

Tu laid before him a tablet of stone whereon the law was engraved.

“For thousands of years this law has been – see, Kull, on the stone it was carved by the primal law makers, so many centuries ago a man might count all night and still not number them all. Neither you, nor any other king, may alter it.”

Kull felt suddenly the sickening, weakening feeling of utter helplessness which had begun to assail him of late. Kingship was another form of slavery, it seemed to him – he had always won his way by carving a path through his enemies with his great sword – how could he prevail against solicitous and respectful friends who bowed and flattered and were adamant against anything new, or any change – who barricaded themselves and their customs with traditions and antiquity and quietly defied him to change – anything?

“Go,” he said with a weary wave of his hand. “I am sorry. But I cannot help you.”

Seno val Dor wandered out of the room, a broken man, if hanging head and bent shoulders, dull eyes and dragging steps mean anything.

III

“I THOUGHT YOU A HUMAN TIGER!”

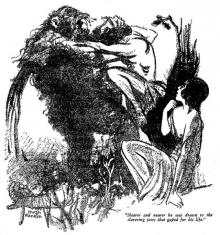

A cool wind whispered through the green woodlands. A silver thread of a brook wound among great tree boles, whence hung large vines and gayly festooned creepers. A bird sang and the soft late summer sunlight was sifted through the interlocking branches to fall in gold and blackvelvet patterns of shade and light on the grass covered earth. In the midst of this pastoral quietude, a little slave girl lay with her face between her soft white arms, and wept as if her little heart would break. The bird sang but she was deaf; the brook called her but she was dumb; the sun shone but she was blind – all the universe was a black void in which only pain and tears were real.

So she did not hear the light footfall nor see the tall broad shouldered man who came out of the bushes and stood above her. She was not aware of his presence until he knelt and lifted her, wiping her eyes with hands as gentle as a woman’s.

The little slave girl looked into a dark immobile face, with cold narrow grey eyes which just now were strangely soft. She knew this man was not a Valusian from his appearance, and in these troublous times it was not a good thing for little slave girls to be caught in the lonely woods by strangers, especially foreigners, but she was too miserable to be afraid and besides the man looked kind.

“What’s the matter, child?” he asked and because a woman in extreme grief is likely to pour her sorrows out to anyone who shows interest and sympathy she whimpered: “Oh, sir, I am a miserable girl! I love a young nobleman –”

“Seno val Dor?”

“Yes, sir.” She glanced at him in surprize. “How did you know? He wishes to marry me and today having striven in vain elsewhere for permission, he went to the king himself. But the king refused to aid him.”

A shadow crossed the stranger’s dark face. “Did Seno say the king refused?”

“No – the king summoned the chief councillor and argued with him awhile, but gave in. Oh,” she sobbed, “I knew it would be useless! The laws of Valusia are unalterable! No matter how cruel or unjust! They are greater than the king.”

The girl felt the muscles of the arms supporting her swell and harden into great iron cables. Across the stranger’s face passed a bleak and hopeless expression.

“Aye,” he muttered, half to himself, “the laws of Valusia are greater than the king.”

Telling her troubles had helped her a little and she dried her eyes. Little slave girls are used to troubles and to suffering, though this one had been unusually kindly used all her life.

“Does Seno hate the king?” asked the stranger.

She shook her head. “He realizes the king is helpless.”

“And you?”

“And I what?”

“Do you hate the king?”

Her eyes flared – shocked. “I! Oh sir, who am I, to hate the king? Why, why, I never thought of such a thing.”

“I am glad,” said the man heavily. “After all, little one, the king is only a slave like yourself, locked with heavier chains.”

“Poor man,” she said, pityingly though not exactly understanding, then she flamed into wrath. “But I do hate the cruel laws which the people follow! Why should laws not change? Time never st

ands still! Why should people today be shackled by laws which were made for our barbarian ancestors thousands of years ago –” she stopped suddenly and looked fearfully about.

“Don’t tell,” she whispered, laying her head in an appealing manner on her companion’s iron shoulder. “It is not fit that a woman, and a slave girl at that, should so unashamedly express herself on such public matters. I will be spanked if my mistress or my master hears of it!”

The big man smiled. “Be at ease, child. The king himself would not be offended at your sentiments; indeed I believe that he agrees with you.”

“Have you seen the king?” she asked, her childish curiosity overcoming her misery for the moment.

“Often.”

“And is he eight feet tall,” she asked eagerly, “and has he horns under his crown, as the common people say?”

“Scarcely,” he laughed. “He lacks nearly two feet of answering your description as regards height; as for size he might be my twin brother. There is not an inch difference in us.”

“Is he as kind as you?”

“At times; when he is not goaded to frenzy by a statecraft which he cannot understand and by the vagaries of a people which can never understand him.”

“Is he in truth a barbarian?”

“In very truth; he was born and spent his early boyhood among the heathen barbarians who inhabit the land of Atlantis. He dreamed a dream and fulfilled it. Because he was a great fighter and a savage swordsman, because he was crafty in actual battle, because the barbarian mercenaries in Valusian armies loved him, he became king. Because he is a warrior and not a politician, because his swordsmanship helps him now not at all, his throne is rocking beneath him.”

“And he is very unhappy.”

“Not all the time,” smiled the big man. “Sometimes when he slips away alone and takes a few hours holiday by himself among the woods, he is almost happy. Especially when he meets a pretty girl like –”

Beyond the Black River

Beyond the Black River Gods of the North

Gods of the North Queen of the Black Coast

Queen of the Black Coast The People of the Black Circle

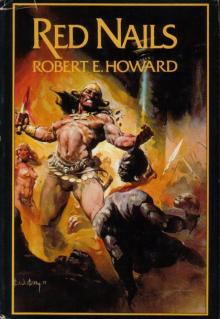

The People of the Black Circle Red Nails

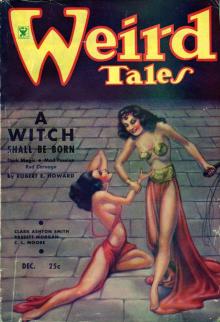

Red Nails A Witch Shall Be Born

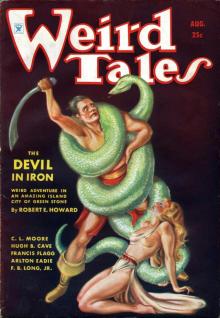

A Witch Shall Be Born The Devil in Iron

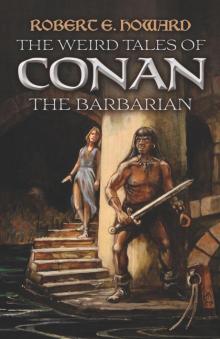

The Devil in Iron The Weird Tales of Conan the Barbarian

The Weird Tales of Conan the Barbarian The Bloody Crown of Conan

The Bloody Crown of Conan The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard

The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard Conan the Conqueror

Conan the Conqueror Conan the Barbarian

Conan the Barbarian Shadows in the Moonlight

Shadows in the Moonlight The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane

The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane Bran Mak Morn: The Last King

Bran Mak Morn: The Last King The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume One: Crimson Shadows

The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume One: Crimson Shadows The Best of Robert E. Howard: Crimson Shadows (Volume 1)

The Best of Robert E. Howard: Crimson Shadows (Volume 1) Black Hounds of Death

Black Hounds of Death Jewels of Gwahlur

Jewels of Gwahlur Shadows in Zamboula

Shadows in Zamboula The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian

The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian The Mythos Tales

The Mythos Tales The Hour of the Dragon

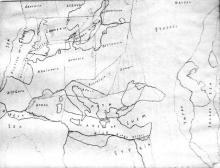

The Hour of the Dragon The Hyborian Age

The Hyborian Age El Borak and Other Desert Adventures

El Borak and Other Desert Adventures The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1 The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1

The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1 The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1 El Borak: The Complete Tales

El Borak: The Complete Tales Kull: Exile of Atlantis

Kull: Exile of Atlantis The Conquering Sword of Conan

The Conquering Sword of Conan The Conan Compendium

The Conan Compendium The Conan Chronicles: Volume 1: The People of the Black Circle

The Conan Chronicles: Volume 1: The People of the Black Circle The Complete Chronicles of Conan: Centenary Edition

The Complete Chronicles of Conan: Centenary Edition Tales of Bran Mak Morn (Serapis Classics)

Tales of Bran Mak Morn (Serapis Classics) Delphi Works of Robert E. Howard (Illustrated) (Series Four)

Delphi Works of Robert E. Howard (Illustrated) (Series Four) Conan the Barbarian: The Stories That Inspired the Movie

Conan the Barbarian: The Stories That Inspired the Movie People of the Dark Robert Ervin Howard

People of the Dark Robert Ervin Howard Grim Lands

Grim Lands Wings in the Night

Wings in the Night Gardens of Fear

Gardens of Fear A Thunder of Trumpets

A Thunder of Trumpets Detective of the Occult

Detective of the Occult Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures

Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures Historical Adventures

Historical Adventures Moon of Skulls

Moon of Skulls The Robert E. Howard Omnibus: 97 Collected Stories

The Robert E. Howard Omnibus: 97 Collected Stories The Pirate Story Megapack: 25 Classic and Modern Tales

The Pirate Story Megapack: 25 Classic and Modern Tales The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 2

The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 2 The Conan Chronicles, Vol. 1: The People of the Black Circle

The Conan Chronicles, Vol. 1: The People of the Black Circle Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures M

Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures M The Complete Chronicles of Conan

The Complete Chronicles of Conan Conan the Barbarian: The Chronicles of Conan (collected short stories)

Conan the Barbarian: The Chronicles of Conan (collected short stories) The Conan the Barbarian Stories

The Conan the Barbarian Stories The Best Horror Stories of

The Best Horror Stories of Tigers Of The Sea cma-4

Tigers Of The Sea cma-4 The Hours of the Dragon

The Hours of the Dragon Conan the Cimmerian: The Complete Tales (Trilogus Classics)

Conan the Cimmerian: The Complete Tales (Trilogus Classics) Collected Western Stories of Robert E. Howard (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics)

Collected Western Stories of Robert E. Howard (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics) The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 1

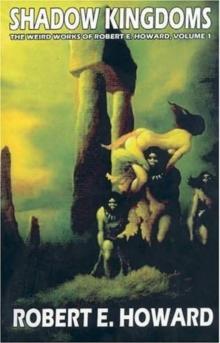

The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 1 Shadow Kingdoms

Shadow Kingdoms