- Home

- Robert E. Howard

The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 2 Page 24

The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 2 Read online

Page 24

“Blow the reason!” said the Old Man, raring back and beaming like a jubilant crocodile. “You licked him – that’s enough. Now we’ll have a bottle opened and drink to Yankee ships and Yankee sailors – especially Steve Costigan.”

“Before you do,” I said, “drink to the boy who stands for everything them aforesaid ships and sailors stands for – Mike of Dublin, an honest gentleman and born mascot of all fightin’ men!”

Black Harps in the Hills

Let Saxons sing of Saxon kings,

Red faced swine with a greasy beard –

Through my songs the Gaelic broadsword sings,

The pibrock skirls and the sporran swings,

For mine is the blood of the Irish kings

That Saxon monarchs feared.

The heather bends to a marching tread,

The echoes shake to a marching tune –

For the Gael has supped on bitter bread,

And follows the ghosts of the mighty dead,

And the blue blades gleam and the pikes burn red

In the rising of the moon.

Norseman reaver or red haired Dane,

Norman baron or English lord –

Each of them reeled to a reddened rain,

Drunken with fury and blind with pain,

Till the black fire spilled from the Gaelic brain

And the steel from the broken sword.

But never the chiefs in death lay still,

Never the clans lay scattered and few –

But a new face rose and a new voice roared,

And a new hand gripped the broken sword,

And the fleeing clans were a charging horde,

And the old hate burned anew!

Brian Boruma, Shane O’Neill,

Art McMurrough and Edward Bruce,

Thomas Fitzgerald – ringing steel

Shakes the hills and the trumpets peal,

Skulls crunch under the iron heel!

Death is the only truce!

Clontarf, Benburb, and Yellow Ford –

The Gael with red Death rides alone!

Lamh derg abu! And the riders reel

To Hugh O’Donnell’s girding steel

And the lances of Tyrone!

Edward Fitzgerald, Charles Parnell,

Robert Emmet – I smite the harp!

Wolfe Tone and Napper Tandy – hail!

The song that you sang shall never fail

While one brain burns with the fire of the Gael

And one last sword is sharp –

Lamh laidir abu! Lamh derg abu!

Munster and Ulster, north and south,

The old hate flickers and burns anew,

The heather shakes and the pikes gleam blue.

And the old clans charge as they charged with you

Into Death’s red grinning mouth!

We have not won and we have not lost –

Fire in Kerry and Fermanagh –

We have broken the teeth in the Saxon’s boast

Though our dead have littered each heath and coast,

And by God, we will raise another host!

Slainte – Erin go bragh.

The Man on the Ground

Cal Reynolds shifted his tobacco quid to the other side of his mouth as he squinted down the dull blue barrel of his Winchester. His jaws worked methodically, their movement ceasing as he found his bead. He froze into rigid immobility; then his finger hooked on the trigger. The crack of the shot sent the echoes rattling among the hills, and like a louder echo came an answering shot. Reynolds flinched down, flattening his rangy body against the earth, swearing softly. A gray flake jumped from one of the rocks near his head, the ricocheting bullet whining off into space. Reynolds involuntarily shivered. The sound was as deadly as the singing of an unseen rattler.

He raised himself gingerly high enough to peer out between the rocks in front of him. Separated from his refuge by a broad level grown with mesquite-grass and prickly-pear, rose a tangle of boulders similar to that behind which he crouched. From among these boulders floated a thin wisp of whitish smoke. Reynold’s keen eyes, trained to sun-scorched distances, detected a small circle of dully gleaming blue steel among the rocks. That ring was the muzzle of a rifle, but Reynolds well knew who lay behind that muzzle.

The feud between Cal Reynolds and Esau Brill had been long, for a Texas feud. Up in the Kentucky mountains family wars may straggle on for generations, but the geographical conditions and human temperament of the Southwest were not conducive to long-drawn-out hostilities. There feuds were generally concluded with appalling suddenness and finality. The stage was a saloon, the streets of a little cow-town, or the open range. Sniping from the laurel was exchanged for the close-range thundering of six-shooters and sawed-off shotguns which decided matters quickly, one way or the other.

The case of Cal Reynolds and Esau Brill was somewhat out of the ordinary. In the first place, the feud concerned only themselves. Neither friends nor relatives were drawn into it. No one, including the participants, knew just how it started. Cal Reynolds merely knew that he had hated Esau Brill most of his life, and that Brill reciprocated. Once as youths they had clashed with the violence and intensity of rival young catamounts. From that encounter Reynolds carried away a knife scar across the edge of his ribs, and Brill a permanently impaired eye. It had decided nothing. They had fought to a bloody gasping deadlock, and neither had felt any desire to “shake hands and make up.” That is a hypocrisy developed in civilization, where men have no stomach for fighting to the death. After a man has felt his adversary’s knife grate against his bones, his adversary’s thumb gouging at his eyes, his adversary’s boot-heels stamped into his mouth, he is scarcely inclined to forgive and forget, regardless of the original merits of the argument.

So Reynolds and Brill carried their mutual hatred into manhood, and as cowpunchers riding for rival ranches, it followed that they found opportunities to carry on their private war. Reynolds rustled cattle from Brill’s boss, and Brill returned the compliment. Each raged at the other’s tactics, and considered himself justified in eliminating his enemy in any way that he could. Brill caught Reynolds without his gun one night in a saloon at Cow Wells, and only an ignominious flight out the back way, with bullets barking at his heels, saved the Reynolds scalp.

Again Reynolds, lying in the chaparral, neatly knocked his enemy out of his saddle at five hundred yards with a .30-.30 slug, and, but for the inopportune appearance of a line-rider, the feud would have ended there, Reynolds deciding, in the face of this witness, to forego his original intention of leaving his covert and hammering out the wounded man’s brains with his rifle butt.

Brill recovered from his wound, having the vitality of a longhorn bull, in common with all his sun-leathered iron-thewed breed, and as soon as he was on his feet, he came gunning for the man who had waylaid him.

Now after these onsets and skirmishes, the enemies faced each other at good rifle range, among the lonely hills where interruption was unlikely.

For more than an hour they had lain among the rocks, shooting at each hint of movement. Neither had scored a hit, though the .30-.30’s whistled perilously close.

In each of Reynold’s temples a tiny pulse hammered maddeningly. The sun beat down on him and his shirt was soaked with sweat. Gnats swarmed about his head, getting into his eyes, and he cursed venomously. His wet hair was plastered to his scalp; his eyes burned with the glare of the sun, and the rifle barrel was hot to his calloused hand. His right leg was growing numb and he shifted it cautiously, cursing at the jingle of the spur, though he knew Brill could not hear. All this discomfort added fuel to the fire of his wrath. Without process of conscious reasoning, he attributed all his suffering to his enemy. The sun beat dazingly on his sombrero, and his thoughts were slightly addled. It was hotter than the hearthstone of hell among those bare rocks. His dry tongue caressed his baked lips.

Through the muddle of his brain burned his hatred of Esau Brill. It had be

come more than an emotion: it was an obsession, a monstrous incubus. When he flinched from the whip-crack of Brill’s rifle, it was not from fear of death, but because the thought of dying at the hands of his foe was an intolerable horror that made his brain rock with red frenzy. He would have thrown his life away recklessly, if by so doing he could have sent Brill into eternity just three seconds ahead of himself.

He did not analyze these feelings. Men who live by their hands have little time for self-analysis. He was no more aware of the quality of his hate for Esau Brill than he was consciously aware of his hands and feet. It was part of him, and more than part: it enveloped him, engulfed him; his mind and body were no more than its material manifestations. He was the hate; it was the whole soul and spirit of him. Unhampered by the stagnant and enervating shackles of sophistication and intellectuality, his instincts rose sheer from the naked primitive. And from them crystallized an almost tangible abstraction – a hate too strong for even death to destroy; a hate powerful enough to embody itself in itself, without the aid or the necessity of material substance.

For perhaps a quarter of an hour neither rifle had spoken. Instinct with death as rattlesnakes coiled among the rocks soaking up poison from the sun’s rays, the feudists lay each waiting his chance, playing the game of endurance until the taut nerves of one or the other should snap.

It was Esau Brill who broke. Not that his collapse took the form of any wild madness or nervous explosion. The wary instincts of the wild were too strong in him for that. But suddenly, with a screamed curse, he hitched up on his elbow and fired blindly at the tangle of stones which concealed his enemy. Only the upper part of his arm and the corner of his blue-shirted shoulder were for an instant visible. That was enough. In that flash-second Cal Reynolds jerked the trigger, and a frightful yell told him his bullet had found its mark. And at the animal pain in that yell, reason and life-long instincts were swept away by an insane flood of terrible joy. He did not whoop exultantly and spring to his feet; but his teeth bared in a wolfish grin and he involuntarily raised his head. Waking instinct jerked him down again. It was chance that undid him. Even as he ducked back, Brill’s answering shot cracked.

Cal Reynolds did not hear it, because, simultaneously with the sound, something exploded in his skull, plunging him into utter blackness, shot briefly with red sparks.

The blackness was only momentary. Cal Reynolds glared wildly around, realizing with a frenzied shock that he was lying in the open. The impact of the shot had sent him rolling from among the rocks, and in that quick instant he realized that it had not been a direct hit. Chance had sent the bullet glancing from a stone, apparently to flick his scalp in passing. That was not so important. What was important was that he was lying out in full view, where Esau Brill could fill him full of lead. A wild glance showed his rifle lying close by. It had fallen across a stone and lay with the stock against the ground, the barrel slanting upward. Another glance showed his enemy standing upright among the stones that had concealed him.

In that one glance Cal Reynolds took in the details of the tall, rangy figure: the stained trousers sagging with the weight of the holstered six-shooter, the legs tucked into the worn leather boots; the streak of crimson on the shoulder of the blue shirt, which was plastered to the wearer’s body with sweat; the tousled black hair, from which perspiration was pouring down the unshaven face. He caught the glint of yellow tobacco-stained teeth shining in a savage grin. Smoke still drifted from the rifle in Brill’s hands.

These familiar and hated details stood out in startling clarity during the fleeting instant while Reynolds struggled madly against the unseen chains which seemed to hold him to the earth. Even as he thought of the paralysis a glancing blow on the head might induce, something seemed to snap and he rolled free. Rolled is hardly the word: he seemed almost to dart to the rifle that lay across the rock, so light his limbs felt.

Dropping behind the stone he seized the weapon. He did not even have to lift it. As it lay it bore directly on the man who was now approaching.

His hand was momentarily halted by Esau Brill’s strange behavior. Instead of firing or leaping back into cover the man came straight on, his rifle in the crook of his arm, that damnable leer still on his unshaven lips. Was he mad? Could he not see that his enemy was up again, raging with life, and with a cocked rifle at his heart? Brill seemed not to be looking at him, but to one side, at the spot where Reynolds had just been lying.

Without seeking further for the explanation of his foe’s actions, Cal Reynolds pulled the trigger. With the vicious spang of the report a blue shred leaped from Brill’s broad breast. He staggered back, his mouth flying open. And the look on his face froze Reynolds again. Esau Brill came of a breed which fights to its last gasp. Nothing was more certain than that he would go down pulling the trigger blindly until the last red vestige of life left him. Yet the ferocious triumph was wiped from his face with the crack of the shot, to be replaced by an awful expression of dazed surprize. He made no move to lift his rifle, which slipped from his grasp, nor did he clutch at his wound. Throwing out his hands in a strange, stunned, helpless way, he reeled backward on slowly buckling legs, his features frozen into a mask of stupid amazement that made his watcher shiver with its cosmic horror.

Through the opened lips gushed a tide of blood, dyeing the damp shirt. And like a tree that sways and rushes suddenly earthward, Esau Brill crashed down among the mesquite-grass and lay motionless.

Cal Reynolds rose, leaving the rifle where it lay. The rolling grass-grown hills swam misty and indistinct to his gaze. Even the sky and the blazing sun had a hazy unreal aspect. But a savage content was in his soul. The long feud was over at last, and whether he had taken his death-wound or not, he had sent Esau Brill to blaze the trail to hell ahead of him.

Then he started violently as his gaze wandered to the spot where he had rolled after being hit. He glared; were his eyes playing him tricks? Yonder in the grass Esau Brill lay dead – yet only a few feet away stretched another body.

Rigid with surprize, Reynolds glared at the rangy figure, slumped grotesquely beside the rocks. It lay partly on its side, as if flung there by some blind convulsion, the arms outstretched, the fingers crooked as if blindly clutching. The short-cropped sandy hair was splashed with blood, and from a ghastly hole in the temple the brains were oozing. From a corner of the mouth seeped a thin trickle of tobacco juice to stain the dusty neckcloth.

And as he gazed, an awful familiarity made itself evident. He knew the feel of those shiny leather wrist-bands; he knew with fearful certainty whose hands had buckled that gun-belt; the tang of that tobacco juice was still on his palate.

In one brief destroying instant he knew he was looking down at his own lifeless body. And with the knowledge came true oblivion.

Old Garfield’s Heart

I was sitting on the porch when my grandfather hobbled out and sank down on his favorite chair with the cushioned seat, and began to stuff tobacco in his old corncob-pipe.

“I thought you’d be goin’ to the dance,” he said.

“I’m waiting for Doc Blaine,” I answered. “I’m going over to old man Garfield’s with him.”

My grandfather sucked at his pipe awhile before he spoke again. “Old Jim purty bad off?”

“Doc says he hasn’t a chance.”

“Who’s takin’ care of him?”

“Joe Braxton – against Garfield’s wishes. But somebody had to stay with him.”

My grandfather sucked his pipe noisily, and watched the heat lightning playing away off up in the hills; then he said: “You think old Jim’s the biggest liar in this county, don’t you?”

“He tells some pretty tall tales,” I admitted. “Some of the things he claimed he took part in, must have happened before he was born.”

“I came from Tennesee to Texas in 1870,” my grandfather said abruptly. “I saw this town of Lost Knob grow up from nothin’. There wasn’t even a log-hut store here when I came. But old Jim Garfield was

here, livin’ in the same place he lives now, only then it was a log cabin. He don’t look a day older now than he did the first time I saw him.”

“You never mentioned that before,” I said in some surprize.

“I knew you’d put it down to an old man’s maunderin’s,” he answered. “Old Jim was the first white man to settle in this country. He built his cabin a good fifty miles west of the frontier. God knows how he done it, for these hills swarmed with Comanches then.

“I remember the first time I ever saw him. Even then everybody called him ‘old Jim.’

“I remember him tellin’ me the same tales he’s told you – how he was at the battle of San Jacinto when he was a youngster, and how he’d rode with Ewen Cameron and Jack Hayes. Only I believe him, and you don’t.”

“That was so long ago –” I protested.

“The last Indian raid through this country was in 1874,” said my grandfather, engrossed in his own reminiscences. “I was in on that fight, and so was old Jim. I saw him knock old Yellow Tail off his mustang at seven hundred yards with a buffalo rifle.

“But before that I was with him in a fight up near the head of Locust Creek. A band of Comanches came down Mesquital, lootin’ and burnin’, rode through the hills and started back up Locust Creek, and a scout of us were hot on their heels. We ran on to them just at sundown in a mesquite flat. We killed seven of them, and the rest skinned out through the brush on foot. But three of our boys were killed, and Jim Garfield got a thrust in the breast with a lance.

“It was an awful wound. He lay like a dead man, and it seemed sure nobody could live after a wound like that. But an old Indian came out of the brush, and when we aimed our guns at him, he made the peace sign and spoke to us in Spanish. I don’t know why the boys didn’t shoot him in his tracks, because our blood was heated with the fightin’ and killin’, but somethin’ about him made us hold our fire. He said he wasn’t a Comanche, but was an old friend of Garfield’s, and wanted to help him. He asked us to carry Jim into a clump of mesquite, and leave him alone with him, and to this day I don’t know why we did, but we did. It was an awful time – the wounded moanin’ and callin’ for water, the starin’ corpses strewn about the camp, night comin’ on, and no way of knowin’ that the Indians wouldn’t return when dark fell.

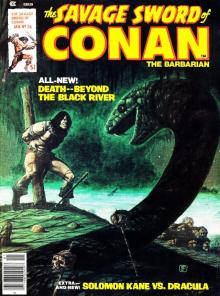

Beyond the Black River

Beyond the Black River Gods of the North

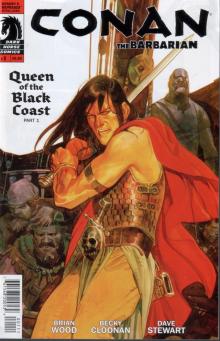

Gods of the North Queen of the Black Coast

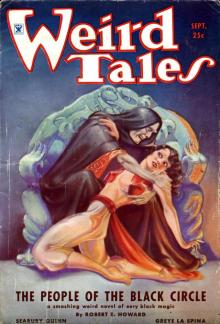

Queen of the Black Coast The People of the Black Circle

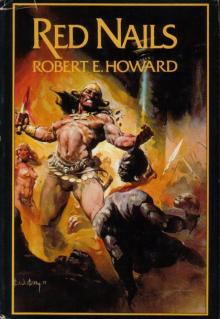

The People of the Black Circle Red Nails

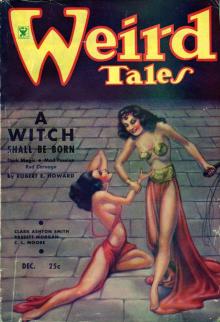

Red Nails A Witch Shall Be Born

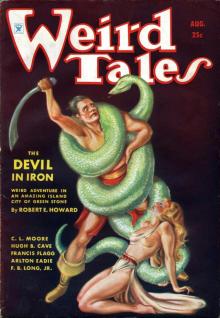

A Witch Shall Be Born The Devil in Iron

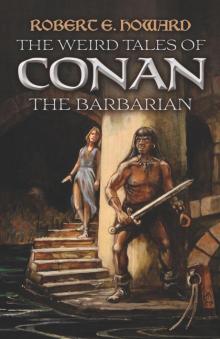

The Devil in Iron The Weird Tales of Conan the Barbarian

The Weird Tales of Conan the Barbarian The Bloody Crown of Conan

The Bloody Crown of Conan The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard

The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard Conan the Conqueror

Conan the Conqueror Conan the Barbarian

Conan the Barbarian Shadows in the Moonlight

Shadows in the Moonlight The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane

The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane Bran Mak Morn: The Last King

Bran Mak Morn: The Last King The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume One: Crimson Shadows

The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume One: Crimson Shadows The Best of Robert E. Howard: Crimson Shadows (Volume 1)

The Best of Robert E. Howard: Crimson Shadows (Volume 1) Black Hounds of Death

Black Hounds of Death Jewels of Gwahlur

Jewels of Gwahlur Shadows in Zamboula

Shadows in Zamboula The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian

The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian The Mythos Tales

The Mythos Tales The Hour of the Dragon

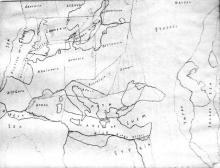

The Hour of the Dragon The Hyborian Age

The Hyborian Age El Borak and Other Desert Adventures

El Borak and Other Desert Adventures The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1 The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1

The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1 The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1 El Borak: The Complete Tales

El Borak: The Complete Tales Kull: Exile of Atlantis

Kull: Exile of Atlantis The Conquering Sword of Conan

The Conquering Sword of Conan The Conan Compendium

The Conan Compendium The Conan Chronicles: Volume 1: The People of the Black Circle

The Conan Chronicles: Volume 1: The People of the Black Circle The Complete Chronicles of Conan: Centenary Edition

The Complete Chronicles of Conan: Centenary Edition Tales of Bran Mak Morn (Serapis Classics)

Tales of Bran Mak Morn (Serapis Classics) Delphi Works of Robert E. Howard (Illustrated) (Series Four)

Delphi Works of Robert E. Howard (Illustrated) (Series Four) Conan the Barbarian: The Stories That Inspired the Movie

Conan the Barbarian: The Stories That Inspired the Movie People of the Dark Robert Ervin Howard

People of the Dark Robert Ervin Howard Grim Lands

Grim Lands Wings in the Night

Wings in the Night Gardens of Fear

Gardens of Fear A Thunder of Trumpets

A Thunder of Trumpets Detective of the Occult

Detective of the Occult Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures

Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures Historical Adventures

Historical Adventures Moon of Skulls

Moon of Skulls The Robert E. Howard Omnibus: 97 Collected Stories

The Robert E. Howard Omnibus: 97 Collected Stories The Pirate Story Megapack: 25 Classic and Modern Tales

The Pirate Story Megapack: 25 Classic and Modern Tales The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 2

The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 2 The Conan Chronicles, Vol. 1: The People of the Black Circle

The Conan Chronicles, Vol. 1: The People of the Black Circle Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures M

Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures M The Complete Chronicles of Conan

The Complete Chronicles of Conan Conan the Barbarian: The Chronicles of Conan (collected short stories)

Conan the Barbarian: The Chronicles of Conan (collected short stories) The Conan the Barbarian Stories

The Conan the Barbarian Stories The Best Horror Stories of

The Best Horror Stories of Tigers Of The Sea cma-4

Tigers Of The Sea cma-4 The Hours of the Dragon

The Hours of the Dragon Conan the Cimmerian: The Complete Tales (Trilogus Classics)

Conan the Cimmerian: The Complete Tales (Trilogus Classics) Collected Western Stories of Robert E. Howard (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics)

Collected Western Stories of Robert E. Howard (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics) The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 1

The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 1 Shadow Kingdoms

Shadow Kingdoms