- Home

- Robert E. Howard

Kull: Exile of Atlantis Page 10

Kull: Exile of Atlantis Read online

Page 10

To Kull, Delcardes was a mysterious and queenly figure, alluring, yet surrounded by a haze of ancient wisdom and womanly magic.

To Tu, chief councillor, she was a woman and therefore the latent base of intrigue and danger.

To Ka-nu, Pictish ambassador and Kull’s closest adviser, she was an eager child, parading under the effect of her show-acting; but Ka-nu was not there when Kull came to see the talking cat.

The cat lolled on a silken cushion, on a couch of her own and surveyed the king with inscrutable eyes. Her name was Saremes and she had a slave who stood behind her, ready to do her bidding, a lanky man who kept the lower part of his face half concealed by a thin veil which fell to his chest.

“King Kull,” said Delcardes, “I crave a boon of you–before Saremes begins to speak–when I must be silent.”

“You may speak,” Kull answered.

The girl smiled eagerly, and clasped her hands.

“Let me marry Kulra Thoom of Zarfhaana!”

Tu broke in as Kull was about to speak.

“My lord, this matter has been thrashed out at lengths before! I thought there was some purpose in requesting this visit! This–this girl has a strain of royal blood in her and it is against the custom of Valusia that royal women should marry foreigners of lower rank.”

“But the king can rule otherwise,” pouted Delcardes.

“My lord,” said Tu, spreading his hands as one in the last stages of nervous irritation, “if she marries thus it is like to cause war and rebellion and discord for the next hundred years.”

He was about to plunge into a dissertation on rank, genealogy and history but Kull interrupted, his short stock of patience exhausted:

“Valka and Hotath! Am I an old woman or a priest to be bedevilled with such affairs? Settle it between yourselves and vex me no more with questions of mating! By Valka, in Atlantis men and women marry whom they please and none else.”

Delcardes pouted a little, made a face at Tu who scowled back, then smiled sunnily and turned on her couch with a lissome movement.

“Talk to Saremes, Kull, she will grow jealous of me.”

Kull eyed the cat uncertainly. Her fur was long, silky and grey, her eyes slanting and mysterious.

“She is very young, Kull, yet she is very old,” said Delcardes. “She is a cat of the Old Race who lived to be thousands of years old. Ask her her age, Kull.”

“How many years have you seen, Saremes?” asked Kull idly.

“Valusia was young when I was old,” the cat answered in a clear though curiously timbred voice.

Kull started violently.

“Valka and Hotath!” he swore. “She talks!”

Delcardes laughed softly in pure enjoyment but the expression of the cat never altered.

“I talk, I think, I know, I am,” she said. “I have been the ally of queens and the councillor of kings ages before even the white beaches of Atlantis knew your feet, Kull of Valusia. I saw the ancestors of the Valusians ride out of the far east to trample down the Old Race and I was here when the Old Race came up out of the oceans so many eons ago that the mind of man reels when seeking to measure them. Older am I than Thulsa Doom, whom few men have ever seen.

“I have seen empires rise and kingdoms fall and kings ride in on their steeds and out on their shields. Aye, I have been a goddess in my time and strange were the neophytes who bowed before me and terrible were the rites which were performed in my worship to pleasure me. For of eld beings exalted my kind; beings as strange as their deeds.”

“Can you read the stars and foretell events?” Kull’s barbarian mind leaped at once to material ideas.

“Aye; the books of the past and the future are open to me and I tell man what is good for him to know.”

“Then tell me,” said Kull, “where I misplaced the secret letter from Kanu yesterday.”

“You thrust it into the bottom of your dagger scabbard and then instantly forgot it,” the cat replied.

Kull started, snatched out his dagger and shook the sheath. A thin strip of folded parchment tumbled out.

“Valka and Hotath!” he swore. “Saremes, you are a witch of cats! Mark ye, Tu!”

But Tu’s lips were pressed in a straight disapproving line and he eyed Delcardes darkly.

She returned his stare guilelessly and he turned to Kull in irritation.

“My lord, consider! This is all mummery of some sort.”

“Tu, none saw me hide that letter for I myself had forgotten.”

“Lord king, any spy might–”

“Spy? Be not a greater fool than you were born, Tu. Shall a cat set spies to watch me hide letters?”

Tu sighed. As he grew older it was becoming increasingly difficult to refrain from showing exasperation toward kings.

“My lord, give thought to the humans who may be behind the cat!”

“Lord Tu,” said Delcardes in a tone of gentle reproach, “you put me to shame and you offend Saremes.”

Kull felt vaguely angered at Tu.

“At least, Tu,” said he, “the cat talks; that you cannot deny.”

“There is some trickery,” Tu stubbornly maintained. “Man talks; beasts may not.”

“Not so,” said Kull, himself convinced of the reality of the talking cat and anxious to prove the rightness of his belief. “A lion talked to Kambra and birds have spoken to the old men of the sea-mountain tribes, telling them where game was hidden.

“None denies that beasts talk among themselves. Many a night have I lain on the slopes of the forest covered hills or out on the grassy savannahs and have heard the tigers roaring to one another across the star-light. Then why should some beast not learn the speech of man? There have been times when I could almost understand the roaring of the tigers. The tiger is my totem and is tambu to me save in self defense,” he added irrelevantly.

Tu squirmed. This talk of totem and tambu was good enough in a savage chief, but to hear such remarks from the king of Valusia irked him extremely.

“My lord,” said he, “a cat is not a tiger.”

“Very true,” said Kull, “and this one is wiser than all tigers.”

“That is naught but truth,” said Saremes calmly.

“Lord Chancellor, would you believe then, if I told you what was at this moment transpiring at the royal treasury?”

“No!” Tu snarled. “Clever spies may learn anything as I have found.”

“No man can be convinced when he will not,” said Saremes imperturbably, quoting a very old Valusian saying. “Yet know, lord Tu, that a surplus of twenty gold tals has been discovered and a courier is even now hastening through the streets to tell you of it. Ah,” as a step sounded in the corridor without, “even now he comes.”

A slim courtier, clad in the gay garments of the royal treasury, entered, bowing deeply, and craved permission to speak. Kull having granted it, he said:

“Mighty king and lord Tu, a surplus of twenty tals of gold has been found in the royal monies.”

Delcardes laughed and clapped her hands delightedly but Tu merely scowled.

“When was this discovered?”

“A scant half hour ago.”

“How many have been told of it?”

“None, my lord. Only I and the Royal Treasurer have known until just now when I told you, my lord.”

“Humph!” Tu waved him aside sourly. “Begone. I will see about this matter later.”

“Delcardes,” said Kull, “this cat is yours, is she not?”

“Lord king,” answered the girl, “no one owns Saremes. She only bestows on me the honor of her presence; she is a guest. As for the rest she is her own mistress and has been for a thousand years.”

“I would that I might keep her in the palace,” said Kull.

“Saremes,” said Delcardes deferentially, “the king would have you as his guest.”

“I will go with the king of Valusia,” said the cat with dignity, “and remain in the royal palace until such time as it shall pleas

ure me to go elsewhere. For I am a great traveller, Kull, and it pleases me at times to go out over the world-path and walk the streets of cities where in ages gone I have roamed forests, and to tread the sands of deserts where long ago I trod imperial streets.”

So Saremes the talking cat came to the royal palace of Valusia. Her slave accompanied her and she was given a spacious chamber, lined with fine couches and silken pillows. The best viands of the royal table were placed before her daily and all the household of the king did homage to her except Tu who grumbled to see a cat exalted, even a talking cat. Saremes treated him with amused contempt but admitted Kull into a level of dignified equality.

She quite often came into his throne chamber, borne on a silken cushion by her slave who must always accompany her, no matter where she went.

At other times Kull came into her chamber and they talked into the dim hours of dawn and many were the tales she told him and ancient the wisdom that she imparted. Kull listened with interest and attention for it was evident that this cat was wiser far than many of his councillors, and had gained more antique wisdom than all of them together. Her words were pithy and oracular and she refused to prophesy beyond minor affairs taking place in the every day life of the palace, and kingdom, save that she warned him against Thulsa Doom who had sent a threat to Kull.

“For,” said she, “I who have lived more years than you shall live minutes, know that man is better without knowledge of things to come, for what is to be will be, and man can neither avert not hasten. It is better to go in the dark when the road must pass a lion and there is no other road.”

“Yet,” said Kull, “if what must be is to be–a thing which I doubt–and a man be told what things shall come to pass and his arm weakened or strengthened thereby, then was not that too, foreordained?”

“If he was ordained to be told,” said Saremes, adding to Kull’s perplexity and doubt. “However, not all of life’s roads are set fast, for a man may do this or a man may do that and not even the gods know the mind of a man.”

“Then,” said Kull dubiously, “all things are not destined, if there be more than one road for a man to follow. And how can events then be prophesied truly?”

“Life has many roads, Kull,” answered Saremes. “I stand at the cross-roads of the world and I know what lies down each road. Still, not even the gods know what road a man will take, whether the right hand or the left hand, when he comes to the dividing of the ways, and once started upon a road he cannot retrace his steps.”

“Then, in Valka’s name,” said Kull, “why not point out to me the perils or the advantages of each road as it comes and aid me in choosing?”

“Because there are bounds set upon the powers of such as I,” the cat replied, “lest we hinder the workings of the alchemy of the gods. We may not brush the veil entirely aside for human eyes, lest the gods take our power from us and lest we do harm to man. For though there are many roads at each cross-roads, still a man must take one of those and sometimes one is no better than another. So Hope flickers her lamp along one road and man follows, though that road may be the foulest of all.”

Then she continued, seeing Kull found it difficult to understand.

“You see, lord king, that our powers must have limits, else we might grow too powerful and threaten the gods. So a mystic spell is laid upon us and while we may open the books of the past, we may but grant flying glances of the future, through the mist that veils it.”

Kull felt somehow that the argument of Saremes was rather flimsy and illogical, smacking of witch-craft and mummery, but with Saremes’ cold, oblique eyes gazing unwinkingly at him, he was not prone to offer any objections, even had he thought of any.

“Now,” said the cat, “I will draw aside the veil for an instant to your own good–let Delcardes marry Kulra Thoom.”

Kull rose with an impatient twitch of his mighty shoulders.

“I will have naught to do with a woman’s mating. Let Tu attend to it.”

Yet Kull slept on the thought and as Saremes wove the advice craftily into her philosophizing and moralizing in days to come, Kull weakened.

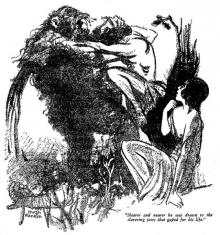

A strange sight it was, indeed, to see Kull, his chin resting on his great fist, leaning forward and drinking in the distinct intonations of the cat Saremes as she lay curled on her silken cushion, or stretched languidly at full length–as she talked of mysterious and fascinating subjects, her eyes glinting strangely and her lips scarcely moving, or not at all, while the slave Kuthulos stood behind her like a statue, motionless and speechless.

Kull highly valued her opinions and he was prone to ask her advice–which she gave warily or not at all–on matters of state. Still, Kull found that what she advised usually coincided with his private wishes and he began to wonder if she were not a mind reader also.

Kuthulos irked him with his gauntness, his motionlessness and his silence but Saremes would have none other to attend her. Kull strove to pierce the veil that masked the man’s features, but though it seemed thin enough, he could tell nothing of the face beneath and out of courtesy to Saremes, never asked Kuthulos to unveil.

Kull came to the chamber of Saremes one day and she looked at him with enigmatical eyes. The masked slave stood statue like behind her.

“Kull,” said she, “again I will tear the veil for you; Brule, the Pictish Spear-slayer, warrior of Ka-nu and your friend, has just been haled beneath the surface of the Forbidden Lake by a grisly monster.”

Kull sprang up, cursing in rage and alarm.

“Ha, Brule? Valka’s name, what was he doing about the Forbidden Lake?”

“He was swimming there. Hasten, you may yet save him, even though he be borne to the Enchanted Land which lies below the Lake.”

Kull whirled toward the door. He was startled but not so much as he would have been had the swimmer been someone else, for he knew the reckless irreverence of the Pict, chief among Valusia’s most powerful allies.

He started to shout for guards when Saremes’ voice stayed him:

“Nay, my lord. You had best go alone. Not even your command might make men accompany you into the waters of that grim lake and by the custom of Valusia, it is death for any man to enter there save the king.”

“Aye, I will go alone,” said Kull, “and thus save Brule from the anger of the people, should he chance to escape the monsters; inform Ka-nu!”

Kull, discouraging respectful inquiries with wordless snarls, mounted his great stallion and rode out of Valusia at full speed. He rode alone and he ordered none to follow him. That which he had to do, he could do alone, and he did not wish anyone to see when he brought Brule or Brule’s corpse out of the Forbidden Lake. He cursed the reckless inconsideration of the Pict and he cursed the tambu which hung over the Lake, the violation of which might cause rebellion among the Valusians.

Twilight was stealing down from the mountains of Zalgara when Kull halted his horse on the shores of the lake that lay amid a great lonely forest. There was certainly nothing forbidding in its appearance, for its waters spread blue and placid from beach to wide white beach and the tiny islands rising above its bosom seemed like gems of emerald and jade. A faint shimmering mist rose from it, enhancing the air of lazy unreality which lay about the regions of the lake. Kull listened intently for a moment and it seemed to him as though faint and far away music breathed up through the sapphire waters.

He cursed impatiently, wondering if he were beginning to be bewitched, and flung aside all garments and ornaments except his girdle, loin clout and sword. He waded out into the shimmery blueness until it lapped his thighs, then knowing that the depth swiftly increased, he drew a deep breath and dived.

As he swam down through the sapphire glimmer, he had time to reflect that this was probably a fool’s errand. He might have taken time to find from Saremes just where Brule had been swimming when attacked and whether he was destined to rescue the warrior or not. Still, he thought that the cat might not have told him, and even if she had assured him of failure, he would

have attempted what he was now doing, anyway. So there was truth in Saremes’ saying that men were better untold then.

As for the location of the lake-battle, the monster might have dragged Brule anywhere. He intended to explore the lake bed until–

Even as he ruminated thus, a shadow flashed by him, a vague shimmer in the jade and sapphire shimmer of the lake. He was aware that other shadows swept by him on all sides, but he could not make out their form.

Far beneath him he began to see the glimmer of the lake bottom which seemed to glow with a strange radiance. Now the shadows were all about him; they wove a serpentine about and in front of him, an ever-changing thousand-hued glittering web of color. The water here burned topaz and the things wavered and scintillated in its faery splendor. Like the shades and shadows of colors they were, vague and unreal, yet opaque and gleaming.

However, Kull, deciding that they had no intention of attacking him, gave them no more attention but directed his gaze on the lake floor, which his feet just then struck, lightly. He started, and could have sworn that he had landed on a living creature for he felt a rhythmic movement beneath his bare feet. The faint glow was evident there at the bottom of the lake–as far as he could see stretching away on all sides until it faded into the lambent sapphire shadows, the lake floor was one solid level of fire, that faded and glowed with unceasing regularity. Kull bent closer–the floor was covered by a sort of short moss-like substance which shone like white flame. It was as if the lake bed were covered with myriads of fire-flies which raised and lowered their wings together. And this moss throbbed beneath his feet like a living thing.

Now Kull began to swim upward again. Raised among the sea-mountains of ocean-girt Atlantis, he was like a sea-creature himself. As much at home in the water as any Lemurian, he could remain under the surface twice as long as the ordinary swimmer, but this lake was deep and he wished to conserve his strength.

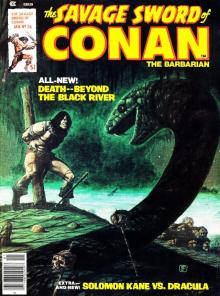

Beyond the Black River

Beyond the Black River Gods of the North

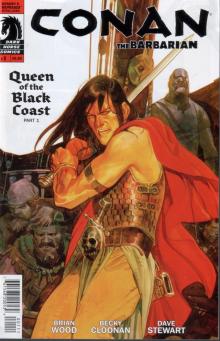

Gods of the North Queen of the Black Coast

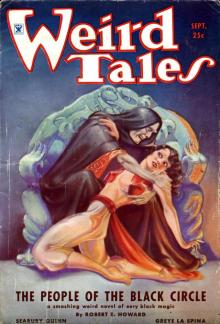

Queen of the Black Coast The People of the Black Circle

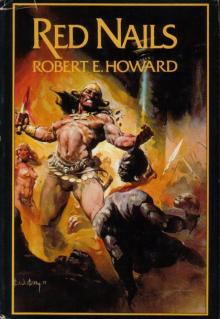

The People of the Black Circle Red Nails

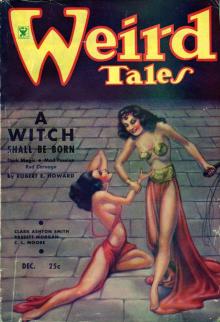

Red Nails A Witch Shall Be Born

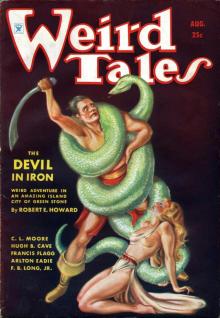

A Witch Shall Be Born The Devil in Iron

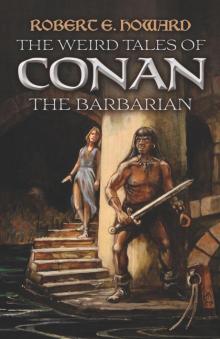

The Devil in Iron The Weird Tales of Conan the Barbarian

The Weird Tales of Conan the Barbarian The Bloody Crown of Conan

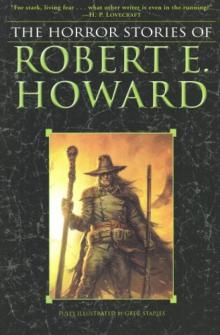

The Bloody Crown of Conan The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard

The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard Conan the Conqueror

Conan the Conqueror Conan the Barbarian

Conan the Barbarian Shadows in the Moonlight

Shadows in the Moonlight The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane

The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane Bran Mak Morn: The Last King

Bran Mak Morn: The Last King The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume One: Crimson Shadows

The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume One: Crimson Shadows The Best of Robert E. Howard: Crimson Shadows (Volume 1)

The Best of Robert E. Howard: Crimson Shadows (Volume 1) Black Hounds of Death

Black Hounds of Death Jewels of Gwahlur

Jewels of Gwahlur Shadows in Zamboula

Shadows in Zamboula The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian

The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian The Mythos Tales

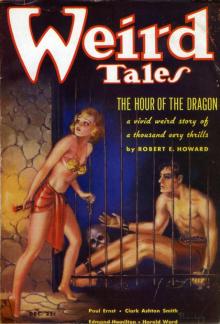

The Mythos Tales The Hour of the Dragon

The Hour of the Dragon The Hyborian Age

The Hyborian Age El Borak and Other Desert Adventures

El Borak and Other Desert Adventures The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1 The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1

The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1 The Best of Robert E. Howard Volume 1 El Borak: The Complete Tales

El Borak: The Complete Tales Kull: Exile of Atlantis

Kull: Exile of Atlantis The Conquering Sword of Conan

The Conquering Sword of Conan The Conan Compendium

The Conan Compendium The Conan Chronicles: Volume 1: The People of the Black Circle

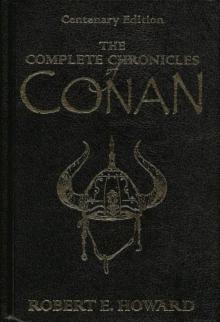

The Conan Chronicles: Volume 1: The People of the Black Circle The Complete Chronicles of Conan: Centenary Edition

The Complete Chronicles of Conan: Centenary Edition Tales of Bran Mak Morn (Serapis Classics)

Tales of Bran Mak Morn (Serapis Classics) Delphi Works of Robert E. Howard (Illustrated) (Series Four)

Delphi Works of Robert E. Howard (Illustrated) (Series Four) Conan the Barbarian: The Stories That Inspired the Movie

Conan the Barbarian: The Stories That Inspired the Movie People of the Dark Robert Ervin Howard

People of the Dark Robert Ervin Howard Grim Lands

Grim Lands Wings in the Night

Wings in the Night Gardens of Fear

Gardens of Fear A Thunder of Trumpets

A Thunder of Trumpets Detective of the Occult

Detective of the Occult Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures

Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures Historical Adventures

Historical Adventures Moon of Skulls

Moon of Skulls The Robert E. Howard Omnibus: 97 Collected Stories

The Robert E. Howard Omnibus: 97 Collected Stories The Pirate Story Megapack: 25 Classic and Modern Tales

The Pirate Story Megapack: 25 Classic and Modern Tales The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 2

The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 2 The Conan Chronicles, Vol. 1: The People of the Black Circle

The Conan Chronicles, Vol. 1: The People of the Black Circle Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures M

Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures M The Complete Chronicles of Conan

The Complete Chronicles of Conan Conan the Barbarian: The Chronicles of Conan (collected short stories)

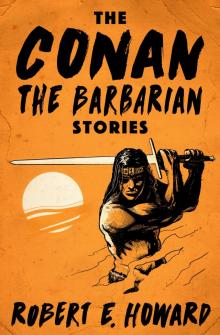

Conan the Barbarian: The Chronicles of Conan (collected short stories) The Conan the Barbarian Stories

The Conan the Barbarian Stories The Best Horror Stories of

The Best Horror Stories of Tigers Of The Sea cma-4

Tigers Of The Sea cma-4 The Hours of the Dragon

The Hours of the Dragon Conan the Cimmerian: The Complete Tales (Trilogus Classics)

Conan the Cimmerian: The Complete Tales (Trilogus Classics) Collected Western Stories of Robert E. Howard (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics)

Collected Western Stories of Robert E. Howard (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics) The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 1

The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume 1 Shadow Kingdoms

Shadow Kingdoms